A Beautiful Mind

When I first started this blog, there were a handful of movies that seemed natural to discuss. Good Will Hunting was my first foray into this group, and was followed by Pi, and later Stand and Deliver. While I have discussed other movies in between, these three are in a class of their own due to the fact that they revolve so centrally around mathematics. There are a couple of notable exceptions on this list, a regrettable fact which I am in the process of correcting. Case in point: today I'd like to take a look at A Beautiful Mind.

More successful than any of the three previous films I listed (from a box office standpoint, mind you, not necessarily a mathematical one), Ron Howard's 2001 biopic of mathematician John Nash won four Academy Awards, including the coveted Best Picture and Best Directing trophies. I saw the film when it came out, but didn't remember much, except for being underwhelmed, and so it was with low expectations that I decided to rewatch the film this weekend...

Stand Up to Questionable Odds

If you went to the movies in Los Angeles this summer, you may have seen the following ad from Stand Up to Cancer, a charitable program whose telethon aired last Friday night. A clear homage to MasterCard's long-running Priceless campaign, this ad swaps out prices for odds, ending with the sobering fact that 1 in 2 men and 1 in 3 women will be diagnosed with some type of cancer in their lifetime.

Presumably, those cancer odds are taken from The American Cancer society, which has the relevant stats posted here. When it comes to some of the other claims in the ad, though, I couldn't help but be skeptical.

Take the bowling claim, for instance. This ad would have you believe that your odds of bowling a perfect game are 1 in 11,500. This seems quite high, even when I consider the fact that I am not a bowling master.

Let's try to reverse-engineer this statistic. To score a perfect game in bowling, one must bowl 12 strikes in a row. Let us suppose that your probability of bowling...

3Dead?

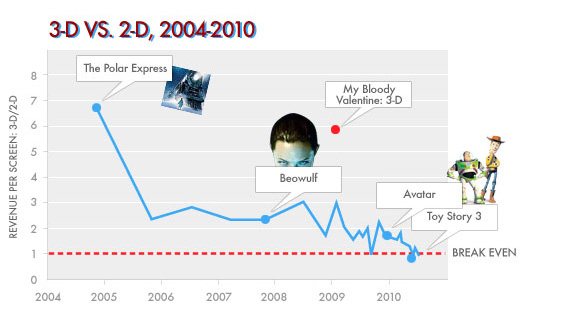

Late last month, Slate ran an interesting article analyzing the performance of 3D movies over the past six years. Titled "Is 3-D Dead in the Water?", the article investigated the success of a 3D film by looking at several films released in 3D and graphing the ratio of their opening weekend revenue from 3D screenings to their opening weekend revenue from 2D screenings. There's a lot of good stuff in the article leading up to this, but the main point is given by the following graph:

Image courtesy of Slate - click the link above to see the original article.

This graph tells you, for example, that during opening weekend for The Polar Express in 2004, the screens showing the film in 3D made nearly 7 times as much money as the screens showing the film in 2D. As you can see, the drop from this film is quite precipitous, and among recent films, it looks as though 3D and 2D versions of a 3D film are making around the same amount of money. Given the extra effort involved in making a film...

Scott Pilgrim Vs. Gravity

More than three weeks after its opening, Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World appears to be limping towards the end of its theatrical run. For whatever reason (some blame marketing, others blame Michael Cera exhaustion, for others the fault lies with a crowded weekend of opening releases) this action comedy with a video game aesthetic and a heart of platinum has failed to find an audience. Critical response has been very positive, and everyone I know who's seen the film has enjoyed it, so it's unfortunate that this level of support hasn't translated into higher revenues.

While I'm sure many people have their own explanations for why this film didn't resonate with a larger crowd, I would like to posit my own: that our culture's math anxiety runs so deep, we instinctively run when there's even a hint of mathematics afoot. For if you look closely enough, you can find some mathematics in this film.

As you probably know, the plot of the film involves Scott Pilgrim fighting his way through...

Weird Al’s Keen Eye

If you follow "Weird Al" Yankovic on Twitter (and really, why wouldn't you?), you may have noticed this picture, which he posted earlier this week along with the tweet "Wow, waffles for just .25 cents? That means I can get 400 for a dollar!!"

Kudos to you, Mr. Yankovic, for spotting what I can only assume to be a mathematical error of the type we've seen before. If this music thing doesn't pan out, maybe you can work for Verizon.

Then again, maybe it's not an error, in which case I can only hope that Weird Al wastes no time in naming this establishment, so that I can patronize it before they catch wise.

(Thanks to Nate for sending this my way!)

The Futurama Theorem

In case you missed it, Futurama was recently resurrected from beyond the television grave, and this summer it began airing new half-hour episodes on Comedy Central. Although it's never reached the height of popularity achieved by its older sibling, The Simpsons, Futurama nevertheless has its own share of dedicated fans. Many of those fans appreciate the differences between this show and The Simpsons, the most obvious of which is the former's futuristic setting and sci-fi influences.

The setting of the show naturally lends itself to math and science jokes, and in this department Futurama does not disappoint. Last week, however, they seriously stepped their game up a notch, by featuring the proof of an original mathematical result as a central feature in the plot of the story.

The mathematics evolves quite organically. In the show, Amy and Professor Farnsworth have created a mind-switching device, which can swap the minds of any two individuals. After a brief discussion, they...

Math of the Rubik's Cube

It's rare for mathematical research to break into the mainstream media. New papers are posted on the arXiv every day, and published in journals all over the world throughout the year, but unless a famous problem is purported to have been solved (in this case, a famous problem is usually one that has a cash prize associated with its solution), knowledge of such advances is only found by those specifically seeking it. Last week, however, there an exception to this general rule was made for a new result concerning the Rubik's cube.

The conclusion, reached by an international team of mathematicians, is that the Rubik's cube can always be solved in 20 moves or less, and that, moreover, their result is in some sense the best possible. This result was featured on the front page of Yahoo News for a couple of days, which I found surprising.

What do I mean by "best possible"? Well, since 1995 it's been known that the minimum number of moves needed to solve a Rubik's cube is at least 20...

Protractors for Some, Miniature American Flags for Others!

Last weekend I went to the Pasadena Flea Market, self-described as "one of the most famous markets in the world." I had not anticipated on finding anything math related, and although I did stumble across an old adding machine, the most surprising find was what greeted me at the door.

R.G. Canning produces the flea market every month, but I have no idea why they were giving away protractors. There's furniture for sale, but I would think rulers would be the preferred measuring device when browsing through such items. Perhaps instead they thought that August would be a good month to get rid of a surplus of protractors, with back to school around the corner? Whatever the case, kudos to R.G. Canning attractions for their protractor giveaway bonanza.

Of course, I'm not sure how many protractors were actually taken. Unfortunately, most people didn't seem interested. Their loss, I suppose.

Race to Where?

Late last month there was apparently a bit of a ruckus over whether or not California should adopt new national education standards as part of a competition among the states dubbed "Race to the Top."

Although Race to the Top (the brain child of education secretary Arne Duncan) hasn't received much media attention, it was one of the many byproducts of last year's economic stimulus act. Recently, though, it's been the subject of more discussion - a relatively detailed article on the program was published over the weekend, for example.

For Californians (and residents of other states, I'm sure), participation in Race to the Top has been met with some controversy. The latest debate, as I mentioned above, has been about education standards. Race to the Top comes with its own set of national education standards, and adopting those standards helps a state's odds of winning some federal education funding. Ergo, the California State Board of Education had to vote on whether or not to adopt...

Top Chef Mathematics

If you like food, Washington DC, hubris, or reality television, then chances are you are a fan of Bravo's cooking competition Top Chef. Every year the show takes a group of aspiring chefs, places them in a house in a new city, and throws weekly challenges their way. Following the Survivor template, every week one chef is voted off, and at the end someone is crowned Top Chef (and given a large check). This season, the action takes place in our nation's capitol.

Now, a show such as this might seem to have very little to do with mathematics. But look, and ye shall find. In the second episode of this past season, the chefs were paired up for one of the challenges. There were 16 chefs at the time, combining to make 8 pairs. The pairing was determined by drawing knives: 16 knives were presented in a knife block, and each had a number on it from 1 to 8. The number was printed on the blade, so each chef would walk to the block, draw a knife, and read the number. The knives were not...

Page 10 of 20