Scott Pilgrim Vs. Gravity

More than three weeks after its opening, Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World appears to be limping towards the end of its theatrical run. For whatever reason (some blame marketing, others blame Michael Cera exhaustion, for others the fault lies with a crowded weekend of opening releases) this action comedy with a video game aesthetic and a heart of platinum has failed to find an audience. Critical response has been very positive, and everyone I know who's seen the film has enjoyed it, so it's unfortunate that this level of support hasn't translated into higher revenues.

While I'm sure many people have their own explanations for why this film didn't resonate with a larger crowd, I would like to posit my own: that our culture's math anxiety runs so deep, we instinctively run when there's even a hint of mathematics afoot. For if you look closely enough, you can find some mathematics in this film.

As you probably know, the plot of the film involves Scott Pilgrim fighting his way through the seven evil exes of Ramona Flowers, the girl of his dreams. And don't let his wiry frame fool you, for Scott Pilgrim has played enough Street Fighter to know how to throw a serious punch. This, combined with his sharp wits, make Scott a deadly opponent.

That's not to say that these fights are a breeze, however. Consider Scott's fight against Ramona's third evil ex, Todd Ingram. Because of his vegan diet, he has certain psychic and telekinetic powers that give him a distinct advantage. Luckily for Scott, though, he is not the sharpest of the evil exes.

Near the end of their battle, in an act of unparalleled physical strength, Todd Ingram executes a most righteous uppercut on Scott Pilgrim that sends him flying through the air. He lands some time later in a pile of garbage. When I watched this scene, one thought came to mind, a thought that I could not dispel for the rest of the movie: how high up did Scott Pilgrim go? Such a question may seem unanswerable, but with some careful measurement and a simple application of the classical equations of motion, an answer is entirely within our grasp.

Consider the setup: Todd and Scott begin in a face off.

Todd then hits Scott and he flies upward with some initial velocity v0. After a certain time, Scott returns to earth.

In the film, Scott remains airborne for approximately 23.6 seconds. If we ignore air resistance, since it takes him about as long to go up as it does to come down, this means he reaches the top of his trajectory around 11.8 seconds into his flight. We can then find the initial velocity, because we know that when Scott Pilgrim reaches the top of his trajectory, his velocity will momentarily be zero.

More specifically, the velocity at any time t is given by

v(t) = v0 + gt,

where g is the acceleration due to gravity, typically approximated by -9.8 m/s2 (since Scott Pilgrim is Canadian, I think it's only fair that we perform this analysis in the standard units of his homeland). In particular, v(11.8) = 0, so we have

v0 = 9.8 x 11.8 = 115.6 m/s,

so Todd sends Scott flying at a speed of approximately 115.6 meters per second, or a whopping 258.6 miles per hour.

Given this initial speed, how high up will Scott travel? For this, we can use the equation governing the vertical position (which is the integral of our velocity equation). If we set Scott's initial height to be 0, then his height at time t is given by

y(t) = v0 t+ gt2/2.

Since we now know the initial velocity, we can plug in values at t = 11.8 (when Scott reaches the highest point). This gives us y(11.8) = 115.6 x 11.8 - 9.8 x (11.8)2/2, which is approximately 681.8 meters (if you prefer, around 2,237 feet).

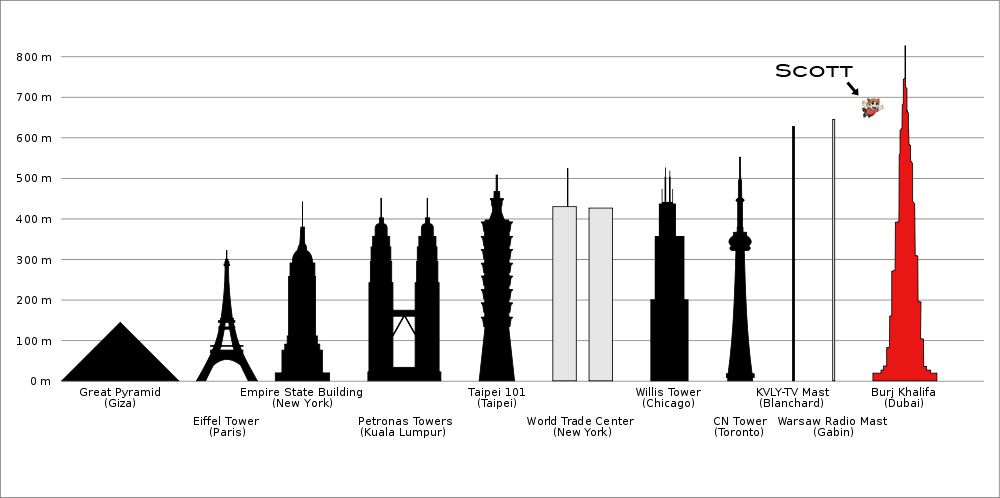

Of course, this number isn't very meaningful without context. As you can see from the picture below (courtesy of Wikipedia), Scott flew way above the Empire State building, and until recently would've flown above the highest skyscrapers in the world. In other words, that punch sent him up fairly high.

Admittedly, this analysis is oversimplified by the fact that we ignored air resistance. If we try to take this into account, what sort of answer will we obtain?

One can obtain analogous answers in the case where air resistance is included, but the mathematics involved quickly becomes more complicated. Let me simply summarize the results, and for those brave souls who want more explanation, I will provide it at the end.

First of all, even though Scott's trip takes 23.6 seconds, with air resistance included we can no longer assume that he reaches the zenith of his trip in half the time. This is because air resistance on the way down will slow his acceleration, so it will actually take longer for him to come down than it did for him to go up. I have calculated that in this case, instead of reaching the peak at 11.8 seconds, he actually reaches it at closer to 8.1 seconds.

As for the peak itself, once you know the time the peak is reached it's not hard to compute. In this case, I found that the peak distance was around 649.1 meters. Lower than in the previous case, but not as much lower as I would've thought.

Perhaps the most interesting thing to note is the change in initial velocity. To keep Scott in the air for 23.6 seconds with no air resistance, we saw that Todd must propel him with an initial velocity of 115.6 m/s. With air resistance, however, to keep Scott in the air for that long requires a much greater initial velocity - around 455.1 meters per second, which is over 1,000 miles an hour. This is also well above the speed of sound, so Scott should have produced a sonic boom as he traveled upwards - the fact that he doesn't in the film shines a light on Canada's best kept secret: it lies inside a perfect vacuum.

Those interested in the details of the air resistance problem, read on. But be careful, there is mathematics ahead!

*

To solve the problem in this case, I began with Newton's second law:

F = ma,

where a = a(t) = v'(t) is Scott's acceleration as a function of time, and v is his velocity.

The drag force provided by air resistance, ignored in our earlier calculations, is directly proportional to the square of the velocity. Moreover, when Scott is traveling upwards, the drag force points in the same direction as the force of gravity. This means that the net force on Scott's body must be -mg - cv2, for some constant c.

When Scott reaches the zenith and begins to descend, the drag force points in the OPPOSITE direction of the gravitational force, so on this side of the trip we see that the net force is -mg + cv2. Note that this net force will shrink in magnitude until the object reaches its terminal velocity, which we will denote by vterm. Since the sum of the forces is 0 when an object reaches terminal velocity, we see that vterm = (mg/c)1/2.

With this setup, we can now prove the following claim.

Claim: Suppose an object is thrown vertically upwards with some initial velocity and lands at a later time tfinal. Then the time at which the object reached the highest point on its trajectory, denoted ttop, satisfies the following equation:

Why is this true? Well, on the upwards trajectory, isolating the acceleration we see that

By separation of variables, this gives

Since , this implies that for some constant k. Solving for v we find that

Moreover, since v(ttop) = 0, we see that k = gttop.

Integrating once more and using the fact that the initial height is 0, we find that for ,

A similar argument works for the downwards trajectory - the only difference is that now the force of gravity and the drag force are in opposite directions. This has the effect of turning the velocity into a function of tanh, rather than tan. The end result is that for , we have

Since y(tfinal) = 0, by integrating once more we can also conclude that for ,

Note that at t = ttop we have two ways of writing the position, depending on which formula for y(t) we'd like to use. Setting the two equations equal at t = ttop, canceling out the common factors of , and exponentiating each side, we are led to the equality

which proves the claim.

This allows us to find ttop numerically given g, tfinal, and vterm. As usual, we approximate g by 9.8 meters per second per second. For the terminal velocity, I consulted this website to find the terminal velocity of a skydiver. I averaged the first four estimates that were in a similar range, and came up with an estimate of 54.7 m/s as a terminal velocity for Scott. Once again, we use 23.6 as the value for tfinal. Graphing for these values of the parameters, you will see that there is a root near t = 8.1. This gives us the time at which Scott achieves his maximum height, and this in turn can be used to find that maximum height, y(ttop), and the initial velocity, .

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus