It's Not Complicated. Or is it?

Though I am hardly AT&T's biggest fan, I can't help but be charmed by their "It's Not Complicated" ad campaign. Each ad features a dapper looking man asking softball questions to a group of young children. Though the ads are meant to elicit mostly meaningless platitudes that AT&T then spins as selling points (e.g. "Faster is Better"), the children's answers and the gentleman's reactions make the ad-watching experience just a little bit more bearable.

In one of the campaign's more recent ads, however, I was disappointed to see a teachable moment go to waste. I suppose this is what happens when you have a cell phone company spokesman in a room full of children instead of an actual teacher. (Though to be fair, the math involved isn't really suitable for elementary school.)

Here's the ad:

In case you don't have time to watch cell phone commercials, here's a transcript of their conversation.

AT&T Guy: What's the biggest number you can think of?

Girl 1: A trillion billion zillion!

AT&T Guy: That's pretty big. How about you?

Boy 1: Ten.

AT&T Guy: ...Okay. How about you?

Boy 2: Infinity!

AT&T Guy: Can you top that?

Girl 2: Infinity and one!

AT&T Guy: Actually, we were looking for infinity plus infinity, sorry.

Girl 1: What about infinity times infinity?

(AT&T Guy's mind is blown.)

There are a number of objections one could raise to the above conversation. I'm not interested in all of them - in particular, I'm not interested in discussing the question of whether or not infinity is a number. What interests me most is whether or not this AT&T Guy gave a fair shake to all of the responses he received.

Google can't get a clear answer on whether infinity is a number or not, though you may be able to if you dig through some of its search results.

Before diving in, we'll need to agree on some terms. Specifically, what do these children mean when they throw around the word "infinity"? Since these children are relatively young, it's safe to assume they have no notion of the different cardinalities of infinity, and instead think of infinity as something akin to a size larger than the largest number. Let's assume that "infinite" in this setting means the size of the set of counting numbers. (In other words, we'll take infinite to mean countably infinite.)

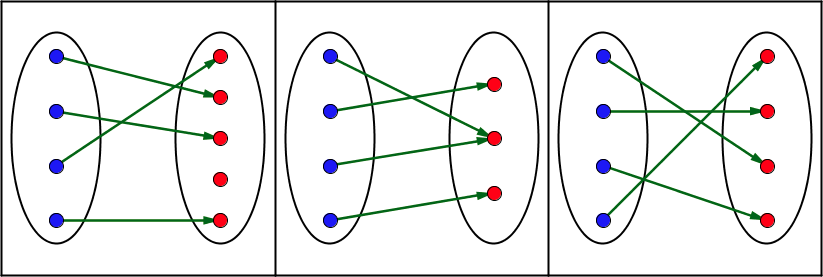

Given this working definition, is there really a distinction between infinity, infinity and one, infinity plus infinity, and infinity times infinity? To answer this question, we need some way to compare sets with infinitely many elements. Thankfully, mathematicians have already thought through these issues. We say two sets are the same size (more precisely, they have the same cardinality) if (1) each element from the first set can be mapped to a unique element from the second set, and (2) every element in the second set gets mapped to by something in the first set. The first condition makes the mapping an injection (also known as 1-to-1), while the second makes the mapping a surjection (also known as onto). Mappings which are both injections and surjections are called bijections. (In other words, a bijection is invertible and vice-versa.)

The jargon can be a little hard to wrap one's head around, so here are some pictures that may help. The first mapping is an injection, but not a surjection. The second is a surjection, but not an injection. Only the third mapping is both.

Here are three mappings (green lines) between two sets (one set of blue points, one set of red points). Can you find an example that is neither injective nor surjective?

Two sets are said to have the same cardinality if there's a bijection between them. For finite sets, this is nothing more than the statement that a set of size n is as large as a set of size m if and only if n = m. For infinite sets it can be a little trickier, but as long as we can find a bijection between two infinite sets, we can say that they have the same size.

So what does this mean for the AT&T commercial? Let's first compare "infinity" to "infinity plus one." To make things concrete, we'll compare two explicit sets: the set of counting numbers {1, 2, 3, ... } to the set of whole numbers {0, 1, 2, 3, ... }. Both sets have a (countably) infinite number of elements, but the set of whole numbers clearly has one element that the set of counting numbers does not: the number zero. So one could argue that if the set of counting numbers is of size infinity, the set of whole numbers is of size infinity plus one.

But these two sizes are really no different! Indeed, we can define a mapping f from the natural numbers to the whole numbers via the formula f(n) = n - 1. This is a bijection because no two counting numbers are mapped to the same whole number (f is injective), and no whole number gets overlooked by this mapping (f is surjective: if m is a whole number, then f(m + 1) = m). In other words, there is a bijection between these two sets, and so they have the exact same cardinality.

What about infinity plus infinity? For this, let's compare the counting numbers {1, 2, 3, ... } to the set of nonzero integers {1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, ...}. Since the second set is essentially two copies of the first (the counting numbers and their opposites), it's not entirely crazy to say that if the first set has size infinity, the second has size infinity plus infinity. But once again, these sets actually have the same cardinality! Here's one example of a bijection in this case:

(I'll leave the verification that this is a bijection up to you.)

In other words, the AT&T guy shouldn't have been so quick to brush off the answer of "infinity and one" in favor of "infinity plus infinity" - these two sizes are really the same.

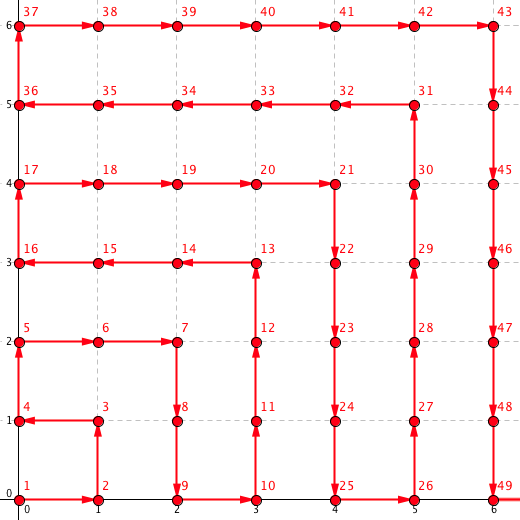

But what about infinity times infinity? That certainly seems larger, right? For an example of such a set, we could consider all the ordered pairs (m, n) where m and n are whole numbers. Since there are infinitely many options for the first coordinate, and infinitely many options for the second, there are, in some sense, infinity times infinity ordered pairs in this set.

Once again, though, this set actually has the same cardinality as the other infinite sets explored here. Writing down an explicit bijection may not be as straightforward in this case, but there are a number of ways to do it. The picture below provides insight into one possible approach:

One way to construct a bijection between the set of whole numbers and the set of ordered pairs of whole numbers.

The conclusion is that all of the infinite sets described in the ad really have the same cardinality. It may not be the most complicated thing in the world, but it's certainly more complicated than AT&T would have us believe.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus