Run for the Ranking

This Saturday, folks from all over the country will be tuning in to the 138th Kentucky Derby. In fact, this year the Kentucky Derby falls on the same day as Cinco de Mayo; undoubtedly the result of this intersection will be a plethora of parties celebrating the melting pot that is America (tacos and mint juleps make for a wonderful combination, I'm sure).

Whenever racing comes up, mathematics can't be far behind. Gambling is always a popular topic: how are the odds for the different racers determined, for example? But this is a question I will save for another time. Today, inspired by horse racing in particular, I'd like to discuss the following classic logic puzzle.

Suppose you have 25 horses and a 5 lane race track. You have no way to record the finishing times of the horses, but you can race up to 5 horses on the track at once and see how quickly the horses finish relative to one another. What's the minimum number of races needed to find the three fastest horses?If you had a stopwatch, you could find the three fastest horses by splitting the 25 horses into groups of 5, racing each group one at a time, and recording their times. In fact, this would provide you with a complete ranking of all the horses from the fastest to the slowest, rather than only an identification of the fastest three. Sadly, without any instruments to measure how quickly a horse completes a race around the track, all we can do is look and see which horses come in first when we race them 5 at a time.

If you haven't seen this puzzle before, it's fun to try and think through yourself. Beware, spoilers abound below!

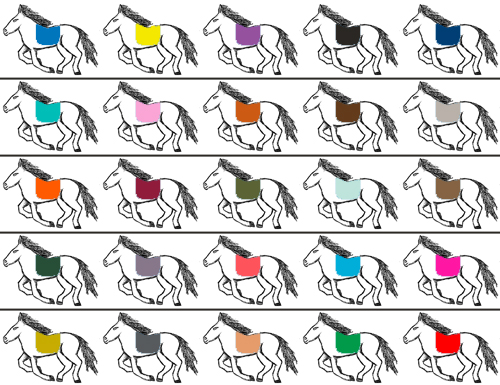

Certainly, the number of races required is more than 5. The best thing to do, it seems, is still to split the horses up into five groups of five and race each group. This is the only way we can get each horse to race once during the first five races; otherwise, after five races there will still be some horses whose ability we know nothing about. So, let's split the horses into groups of five and race each group. Suppose we then organize the results of the races in the following table:

Here I've let each row represent a single race, and the horses are ranked by how they placed. For example, the first race consisted of horses in the top row. Within that race, the horse with the blue saddle came in first, followed by the horse with the yellow saddle, then the purple saddle, then the black saddle, with the horse in the dark blue saddle coming in last. We don't know any of their individual racing times, and so we only know how a horse compares relative to the other horses in the same row.

After five races, what can we conclude? Well, since we want to identify the fastest three horses, we can easily eliminate the fourth and fifth place finishers in each race; each one of these horses is slower than at least three others. This allows us to narrow the field of horses from 25 down to 15.

Now within each row, we know faster horses are on the left and slower horses are on the right. But we have no way to compare horses across the columns. It may be that the first row consists of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd fastest horses, but it's just as likely that the first row consists of the 13th, 14th, and 15th fastest horses. Without being able to compare the columns, we can't draw any further conclusions.

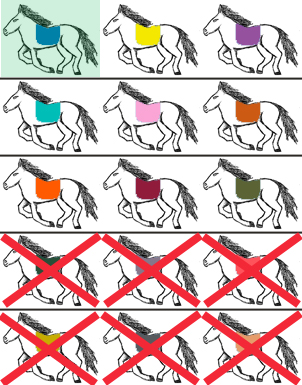

So, it makes sense to take a horse from each column and create a sixth race. It also makes sense to race the winners from all the previous races, because the winner among all the winners will be the fastest horse, and we will then only have to find the 2nd and 3rd fastest horses. After racing the first column of horses, suppose the ranking is as in the picture (i.e. blue horse in first, teal horse in second, orange in third, etc). If this is not the case, we can always interchange rows so that the first column is ranked according to the outcome of the sixth race. Our picture now looks like this:

The fastest horse is now in green.

We don't need to race the horse in the upper left corner anymore, since we know it's the fastest. In fact, we know even more: just as in the previous case, we can eliminate the fourth and fifth place finishers from the sixth race. But if we cross out the first horse in the fourth row, we can cross out all the horses to the right, since they are all slower! The same is true for the fifth row. This reduces the pool of horses from 15 to 9 (or rather, from 14 to 8, since we no longer need to race the fastest horse):

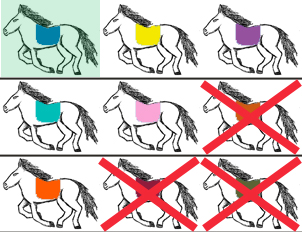

Are there any other horses we can eliminate? Thankfully, the answer is yes! We know that the horse on the left in the second row can, at best, be the second fastest horse. But this means the horses to the right of it can, at best, be the third and fourth fastest, respectively. Since we're not interested in the fourth fastest horse, we can safely eliminate the third horse in the second row.

Similarly, the horse on the left in the third row can, at best, be the third fastest horse (since it was slower than the horses above it). This means the other horses in the third row can be no faster than the fourth and fifth fastest horses. Therefore, both horses can safely be eliminated. Removing these horses from contention leaves us with the following picture:

In other words, we have identified the fastest horse, and eliminated all but five remaining horses. There's no way to determine the second and third fastest horses based on the information we have, but since our track has exactly five lanes, we can hold a seventh race among the five remaining horses. The first and second place finishers of this final race will be the second and third fastest horses overall.

So, the answer to this puzzle appears to be 7. Technically, I suppose I haven't shown that it's impossible to do in six races, but if you play around with these ideas you'll quickly convince yourself that six races is insufficient. The nice thing about this problem is that it is easy to ask about generalizations: what happens if you change the number of horses, number of lanes, or number of rankings you wish to determine? Here's a discussion of a generalization to finding the best k horses out of (k - 1)2(k + 2)2/4 horses total, if you have a race track with (k - 1)(k + 2)/2 lanes. Though it doesn't look like it, this is a fairly natural generalization of the case discussed here (in the above case, k = 3).

Of course, this is a fairly idealized situation, since it assumes the horses will finish the race with the same time whenever they run. In real life, there will be some variance in their finishing times, and in turn this will make the determination of the three "best" horses a bit more nuanced. This leads naturally into the mathematics of ranking, a topic I will turn my attention to in my next post!

(H/t to Dayna for her killer horse drawings).

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus