How Powerful is the Pyramid?

My love of NBC comedies has, by now, been well established. Today I'd like to return to The Office, for although Steve Carrell's absence may have hurt the ratings, it certainly has not diminished the potential for the show to inspire some mathematical thinking.

If you have not been watching recently, this season marked the debut of the company's first ever tablet computer, dubbed the Pyramid. The Pyramid made its first appearance early in the season (and was also featured in on Wired), and has since been joined by a smartphone counterpart known as the Arrowhead. Here's an image of Dwight touting the new tablet.

On the face of it, the tablet is ridiculous (this fact is eventually sort of addressed later on in the season). Who wants to use a triangular shaped tablet to look at pictures or watch movies? The reason I bring this up is that from a strictly mathematical standpoint, there are reasons to view the design with quite a bit of skepticism.

Why is this the case? Well, let's think about the practical matter of building a tablet like the one seen above. There is a certain cost involved in producing such a charming device; let us focus on the cost associated with the metal frame. Suppose the cost of the frame is in direct proportion to the amount of material used. If we want a large screen (and let's face it, who doesn't?), then we have a bit of a balancing act to play: we'd like to have a large screen, but we also want a small border so that we don't have to spend a lot on material for the frame. In other words, if we have a certain amount of material for the frame, we would like to find the largest area possible that we could enclose with that particular length of material.

For ease of computation, let's suppose the border of the pyramid is composed of a strip of metal one meter across, i.e. the perimeter of the pyramid is 1. If we are beholden to the "pyramid" gimmick, let's ask: how can we make an isosceles triangle with the largest area if its perimeter must be 1 meter? I'm sticking to isosceles triangles only since we don't usually think of pyramids as being lopsided.

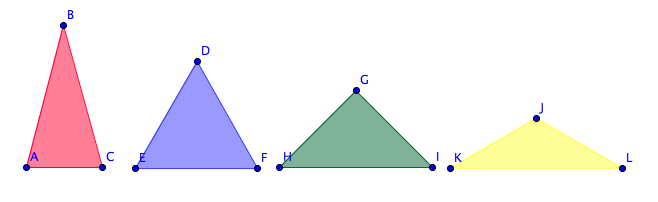

Different isosceles triangles with perimeter equal to 1. The top angles are 30°, 60°, 90°, and 120°, respectively. Which do you think has the largest area?

If we really want to see which isosceles triangle with perimeter equal to one has the largest area, we need to find a formula for the area. One convenient way to organize such triangles is by the angle formed at the top of the triangle. For any angle between 0° and 180°, we can construct an isosceles triangle of perimeter 1 - what is the area as a function of the angle?

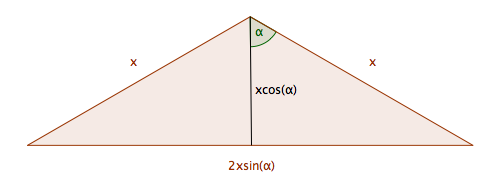

To answer this question, consider the following diagram:

A general isosceles triangle has two sides of the same length, which we will denote x. Let's cut the triangle in half, so that on the right hand side we have a right triangle with an angle α. By the definition of sine and cosine, it follows that the line splitting the isosceles triangle in two has length xcos(α)$, and half of the base of the isosceles triangle has length xsin(α), so that the entire base of the isosceles triangle is twice as large, or 2xsin(α).

We can use this to find the area of the triangle as a function of the angle α. We know the perimeter of the triangle should equal 1, so from the above diagram this means

1 = x + x + 2xsin(α) = 2x(1 + sin(α)).

Solving for x, we then obtain

x = 1/(2(1 + sin(α))).

On the other hand, as any good geometry student should recall, the area of a triangle is equal to half the base times the height. Since the base and height can be read from the above figure, we see the area must therefore equal

x2sin(α)cos(α)

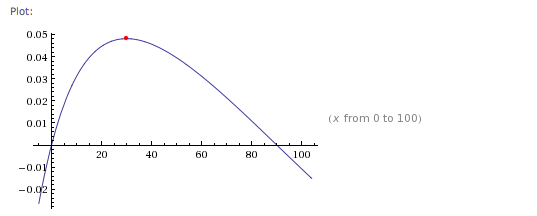

So to find the largest area, we can plot the graph of this function and see where it attains a maximum (or, if you want to be fancy about it, you can use some calculus).

The graph of the above function looks like this (thanks, WolframAlpha):

The maximum occurs when α equals 30° - in other words, the top angle of the isosceles triangle is 60°, which means the triangle itself is equilateral! So the largest area occurs for an equilateral triangle - in this case, the area equals , or roughly 0.0481.

But the Pyramid in The Office doesn't look like an equilateral triangle. In fact, the top angle looks to be closer to a 90° angle. If this is the case, then $latex α would be 45°, and the area is but a meager , or around 0.0429. In other words, the designers of the Pyramid could have increased the area by roughly 12% with a better triangle design.

But why restrict to triangles in the first place? Let's suppose the designers had instead decided to stick with convention and go with a tablet whose screen ratio was 4:3 (like the iPad, for example). Since the perimeter is 1, this would mean the length of the tablet would have to equal 4/14, and the height would have to equal 3/14. Since the area is the length times the width, this would give a total area of 12/196, or 3/49; this is around 0.612. In other words, this change would bring about a 27% increase in area compared to the optimal pyramid design, and a nearly 43% increase in area compared to the design featured on the show.

Of course, there's nothing sacred about the 4:3 ratio - by considering an arbitrary rectangle, can you find the one that maximizes the area if the perimeter equals 1?

We can continue exploring this problem with a variety of geometric shapes. At some point, it is natural to ask: given a fixed perimeter of 1, what closed plane curve maximizes the area contained by the perimeter? This is the famous isoperimetric inequality, and it has a solution. Namely, if you have a closed figure of perimeter 1, the largest area you can enclose is 1/(4π), or approximately 0.0796. Moreover, you get this largest area precisely when the closed figure is a circle. Said another way, for a given perimeter, the circle encloses the largest possible area.

Had the designers of the Pyramid opted for a circular theme instead (e.g. the Orb), they could have increased the area of the screen by over 65% compared to using an equilateral triangle, and by over 85% compared to the designed used in the show! No wonder the folks on The Office are always worried about losing their jobs. Then again, it's an open debate as to whether a triangular or circular tablet design is more useless.

I readily admit that this analysis is somewhat oversimplified. We've considered the cost of the tablet's frame, for example, but completely ignored the cost of producing the screen itself. But sometimes in the interest of finding some nice mathematics, sacrifices must be made. I trust you will forgive me for this small indiscretion.

(Thanks to Karim from Mathalicious for the conversation which inspired this post!)

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus