Car Talk Mathematics

Happy 2012! I hope you all has a restful and calorie-filled holiday. For my part, the holidays typically involve a fair amount of driving, and ergo, a fair amount of listening to podcasts. To that end, I'd like to ease into a new year of mathematics by considering a simple puzzle, one which was featured recently on NPR's Car Talk. If you are not fortunate enough to have listened to this show, it centers on two brothers from Cambridge, Massachusetts, affectionately known as Click and Clack, the Tappet Brothers (though their real names are Tom and Ray Magliozzi). Each week, in between a fair amount of good-natured banter, the brothers field a variety of automotive questions from callers nationwide.

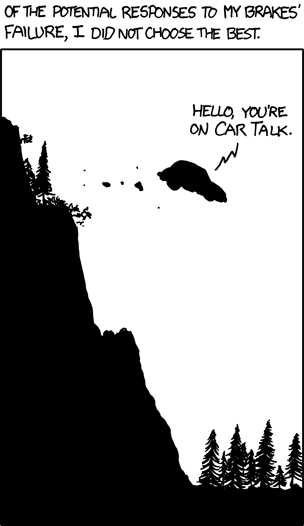

Even XKCD is on the Car Talk bandwagon! (Click the image to go to the source.)

Most significant to our present discussion, however, is Car Talk's weekly diversion known as the Puzzler. Each week, the brothers read a Puzzler (i.e. a brain teaser) to their listeners and request solutions. The Puzzler's solution is revealed the following week, and a new Puzzler is then presented; moreover, one of the correct listener submissions is chosen at random, and the winner receives a gift certificate for some Car Talk schwag. While these puzzles are sometimes car-related, this is not a prerequisite, and indeed the puzzler I would now like to discuss makes no mention of cars.

Here's the puzzle, with wording modified slightly from Car Talk's website: Suppose there are 20,000 lights in a row, all turned off. One person comes through and pulls the cord on every light, turning each of them on. A second person then comes through and pulls the cord on every second light. A third person then pulls the cord on every third light, and so on. After the 20,000th person has gone through the room, which lights are turned on?

This problem also goes by the name of the Locker Problem, with open and shut lockers substituting for on and off lights. But no matter how you contextualize the problem, the solution is the same. To get some idea of what the answer should be, let's consider what happens just for the first few (say, 10) light bulbs. Feel free to think about this problem on your own before continuing on!

After the first person walks through the room, all the light bulbs are on. So, the first 10 light bulbs will look like this:

After every second cord is pulled, half the lights will be on, and half will be off:

Now here's where the fun begins. When every third cord is pulled, off lights will turn on, and on lights will turn off. This means that the arrangement of the first ten lights will look like this:

And, when every fourth cord is pulled, we get the following picture:

You can probably fill in the rest. Note that when every 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, or 10th cord is pulled, only one light in first 10 switches, so most of the work is already done. In the end, the string of the first 10 lights will look like this:

Here we see that three of the first ten lights remain lit: the 1st, 4th, and 9th. The astute reader will note that 1, 4, and 9 all share a common property; they are all perfect squares (1 = 12, 4 = 22, 9 = 32). The question to be asked, of course, is whether this pattern continues, and if it does, why?

To answer these questions we'll need to think a bit more deeply about what's going on. First, when does a given light bulb in our string of 20,000 get its cord pulled? Extrapolating from the first few cases, we see that if a person goes through the chain and pulls every dth cord, then the light bulbs with their cords pulled are precisely the ones whose numbers are multiples of d. Therefore, the nth bulb's cord is pulled once for every divisor of n. More concretely, we see for example that the 12th light bulb will have its cord pulled 6 times: by the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 12th person, since 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 12 are precisely the divisors of 12.

What does this divisibility information tell us about the status of a given light bulb? Since all the lights start in the off position, we see that a light will be off at the end if its cord is pulled an even number of times, and it will be on at the end if its cord is pulled an odd number of times. In other words, the nth light will be on at the end of this process precisely when n has an odd number of divisors.

All we need to do now is convince ourselves that the numbers with an odd number of divisors are precisely the squares. There are a couple of ways to do this.

Way 1: Pick your favorite whole number n. For any divisor d of n, n/d is also a divisor (for example, if n = 30, the fact that 5 is a divisor immediately tells us that 30/5 = 6 is a divisor too). In this way, we can naturally count up all the divisors of n in pairs. Because of this, the only way we can have an odd number of divisors is if one of the pairs has the same number repeated twice, i.e. if for some divisor d, d and n/d are equal. But if they are equal, this means that n = d2, in other words, n is a square.

Way 2: By the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, Any positive whole number n > 1 can be written in an essentially unique way as a product of prime numbers, i.e. for any n > 1 we can write

where the numbers pi are primes, and the exponents ki are greater than zero (for example, 180 = 22 · 32 &midot; 5). In particular, any divisor of n must be composed of the same primes as n itself, so that if d is a divisor, we can write

where each exponent mi is no larger than ki (for example, 12 is a divisor of 180 but 24 isn't, since 2 goes into 24 three times but into 180 only twice).

How many divisors are there? Well, p1 could divide d as few as 0 times, or as many as k1 times - we have k1 + 1 different ways to choose the exponent on p1, corresponding to the numbers 0, 1, 2, ..., up to k1. Similarly, we have k2 + 1 different ways to choose the exponent on p2, and so on for each prime, so that there are kr + 1 different ways to choose the exponent on pr. By the fundamental counting principle, this means that the number of divisors of n is equal to

(k1 + 1)(k2 + 1)...(kr + 1).

Remember that our light will be on only if the number of divisors is odd, in other words, only if the above product is odd. Notice that if any term in the above product is even, the product itself will be even - so in order for the product to be odd, each term in the product must be odd. Since each ki + 1 must be odd, this means that each exponent ki must be even. But if each ki is even, then ki/2 is always a whole number, so

is a whole number whose square is equal to n. Hence, once again we conclude n is a square.

There are plenty of variants to this problem worth pondering - for example, what if people only come in and pull every dth cord only for d prime? Or, what if instead of the 2nd person pulling every 2nd cord, and the third person pulling every 3rd cord, the second person pulls every 2nd cord twice, the third person pulls every 3rd cord three times, and so on? No doubt you can come up with some variants on your own as well.

If you prefer the locker version, here's an interactive site where you can watch with satisfaction as lockers open and close. No matter what model you use, though, this is a cute little problem on integers and their divisibility, and the result can be surprising for first time viewers. So kudos to Car Talk for discussing this problem on a national stage! (Kudos also to Tom for drawing my attention to this particular episode of the program.)

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus