An Introduction to Pumpkin Chunkin'

In a recent episode of ABC's Modern Family, Cameron and Mitchell (the show's unambiguously gay duo) are with some friends talking about Thanksgiving when Cameron decides to tell a story from his youth which, in his opinion, is quite compelling. Mitchell knows better, but doesn't have the heart to tell him that this particular story suffers from some basic structural flaws. As Mitchell puts it, the story can be summarized as follows: "Once Cam and his friends tried to slingshot a pumpkin across a football field. Three seconds. That's all you need to tell that story."

Needless to say, Cameron's version of the story is much more embellished. In his rendition, their experiment was a success; as he puts it, the pumpkin flew across the field, "goal post to goal post."

When I first heard him say this, my initial thought was "Is Cameron telling the truth?" How likely is it that a pumpkin, launched from a slingshot at one end of a football field, could sail through the air to land on the other side? Note that his story actually ends with the pumpkin falling through the sun roof of someone's car - this outcome is, of course, highly implausible, and therefore casts a shadow of doubt upon the entire story. While the sunroof claim would be difficult to verify, one can at least use some basic math and physics to test the plausibility of the first portion of the story.

We would like to be able to find a formula for the distance Cameron's pumpkin should travel. Key to our analysis is the conservation of energy principle, and Hooke's Law. In particular, we will assume that the slingshot behaves like a spring, i.e. the potential energy it stores is proportional to the square of the displacement (for example, stretching the slingshot two meters gives you four times the potential energy as stretching it one meter). So, if Cameron and his friends stretched the slingshot a distance of x meters, the slingshot would then store a potential energy of ½kx2, where k is the spring constant and depends on the physical properties of the slingshot.

Now let us invoke the conservation of energy principle: when the slingshot is released, suppose all that stored potential energy will be converted into the kinetic energy of the pumpkin. The formula for the kinetic energy of an object is ½mv2, where m is the object's mass, and v is the object's velocity. So, when the pumpkin is released, by conservation of energy, this kinetic energy should be the same as the potential energy the system had before we chunked the pumpkin. In other words,

½kx2 = ½mv2,

which, with a bit of algebra, tells us that the initial velocity of the pumpkin when it comes out of the slingshot must be x√mk.

These poor little guys have no idea what's in store for them.

So we have an equation for the velocity of the pumpkin in terms of the spring constant k, the distance x we pull the slingshot, and the mass m of the pumpkin. Let's not forget our main goal, though - what we're ultimately interested in isn't a formula for the initial velocity of the pumpkin, but rather the distance the pumpkin travels. With a little more physics, it's not hard to get from one of these pieces of information to the other.

More specifically, we have a very good understanding of projectile motion. As I've discussed before, if one ignores air resistance (as we will do for now), all the equations of projectile motion can be derived from the fact that the acceleration due to gravity is a constant, g ≈ 9.8 meters per second per second.

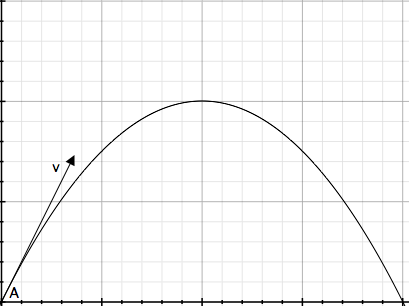

Using this fact, suppose you throw an object with an initial velocity v0 at an angle θ to the horizontal. Then if one sets the initial position of the object to have coordinates (0,0), the x-coordinate of the object at any time t will be given by tv0cos(θ), and the y-coordinate of the object at any time t will be given by tv0cos(θ) – ½gt2. Using these formulas and a bit more algebra, one can determine that the distance d an object will travel in the x direction can be written in terms of the initial velocity, the angle θ, and g, via the formula

d=gv02sin(2θ).

Example trajectory of an object shot with an initial velocity v at an angle A. The distance the object travels in the x direction is given by the above formula.

To recap: we have the distance as a function of the initial velocity, the angle the pumpkin is shot from, and the acceleration due to gravity. We also have the initial velocity in terms of the distance the slingshot is stretched, the mass of the pumpkin, and the spring constant. Combining these two formulas, we find that

d=mgkx2sin(2θ),

and we now have the desired formula for the distance the pumpkin travels.

Let's check Cameron's story against this formula. If the pumpkin really went from goal post to goal post, the distance it traveled in the x direction must have been at least 120 yards (100 yards for the field of play, plus 10 yards for each end zone). This is roughly 109.7 meters. Therefore, we must have d ≥ 109.7.

On the right side of the equation, the term sin(2θ) is maximized when θ equals 45°, and in this case sin(90) = 1. So after making this simplification, we see that in order for Cameron's story to be true, it must be the case that

The acceleration due to gravity is known, but we need to provide estimates for m, k, and x. The mass m is the easiest to estimate; let's say the pumpkin is around 10 pounds (roughly 4.5 kilograms). To be generous, we'll even round down to 4 kilograms. What about the distance the slingshot is stretched? Based on the slingshot used in the episode, it's unlikely the slingshot in Cameron's story would have been stretched more than 2 meters or so, but let's again be generous and say it's stretched 3 meters. Plugging in these values, we would have:

k ≥ 109.7 · 4 · 9.8 ÷ 9 ≈ 478,

where the units on k are Newtons per meter. Since one pound is approximately 4.45 newtons, this is saying that the spring constant is about 107 pounds per meter - in other words, for each meter you stretch the slingshot, you need to exert 107 pounds of force. To put it another way, to stretch the slingshot 3 meters or more, you'd need to exert 321 pounds of force.

This seems like quite a lot, though Cameron is a large fellow. But recall we were being generous, both in our computation of the spring constant and in our estimate of the pumpkin size. We also neglected air resistance in this model, but air resistance probably has a non-negligible impact here - not only will it slow down the pumpkin's forward motion, but it also decreases the optimal angle from 45°. So in a real world situation, I'd have to remain skeptical of Cameron's story. On the other hand, these calculations don't necessarily rule it out entirely (though a more sophisticated analysis might).

For more on the physics of pumpkin chunkin', here's an article from last year courtesy of Wired. For related trajectory issues, Angry Birds also provides plenty of fodder.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus