Moneyball

This weekend, mathematics played a supporting role to Brad Pitt in one of fall's first critical darlings, Moneyball. Based on the Michael Lewis book of the same name, the film profiles the Oakland A's during their 2002 bid for World Series glory. What allegedly separates their story from the story of other teams during that season is the way General Manager Billy Beane, played by Brad Pitt, deals with the budget constraints imposed on him by the team's owners.

With a payroll roughly a third the size of the Yankees', Beane understood that the playing field was not a level one from an economic standpoint. What's more, at the end of the 2001 season, three of the A's star players left Oakland for bigger paychecks. To fill the void, the film (and book) show how Beane took a more analytic approach, and used statistical analysis to uncover players who were undervalued and could be purchased for much less than they were worth. Beane, together with Paul DePodesta (Peter Brand in the film, and played by Jonah Hill), used a sabermetric approach to lead the A's to a league-leading 103 wins for the season. While their first-place ranking for number of wins that year was shared with the Yankees, they spent much less per win than their New York counterparts (the A's spent the least per win, while the Yankees spent the third most). Here's a table comparing the teams; the payroll numbers are taken from here, and differ slightly from the numbers that appear in the book.

| Team | Wins | Losses | Payroll | Cost Per Win (millions) |

| Oakland Athletics | 103 | 59 | $40,004,167 | $0.388 |

| Minnesota Twins | 94 | 67 | $40,225,000 | $0.428 |

| Montreal Expos | 83 | 79 | $38,670,500 | $0.466 |

| Florida Marlins | 79 | 83 | $41,979,917 | $0.531 |

| Cincinnati Reds | 78 | 84 | $45,050,390 | $0.578 |

| Pittsburgh Pirates | 72 | 89 | $42,323,599 | $0.588 |

| Los Angeles Angels | 99 | 63 | $61,721,667 | $0.624 |

| Tampa Bay Rays | 55 | 106 | $34,380,000 | $0.625 |

| San Diego Padres | 66 | 96 | $41,425,000 | $0.628 |

| Chicago White Sox | 81 | 81 | $57,052,833 | $0.704 |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 80 | 81 | $57,954,999 | $0.724 |

| Houston Astros | 84 | 78 | $63,448,417 | $0.755 |

| Kansas City Royals | 62 | 100 | $47,257,000 | $0.762 |

| St. Louis Cardinals | 97 | 65 | $74,660,875 | $0.770 |

| Colorado Rockies | 73 | 89 | $56,851,043 | $0.779 |

| S.F. Giants | 95 | 66 | $78,299,835 | $0.824 |

| Seattle Mariners | 93 | 69 | $80,282,668 | $0.863 |

| Milwaukee Brewers | 56 | 106 | $50,287,833 | $0.898 |

| Baltimore Orioles | 67 | 95 | $60,493,487 | $0.903 |

| Atlanta Braves | 101 | 59 | $93,470,367 | $0.925 |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 78 | 84 | $76,864,333 | $0.985 |

| Detroit Tigers | 55 | 106 | $55,048,000 | $1.001 |

| L.A. Dodgers | 92 | 70 | $94,850,953 | $1.031 |

| Arizona D'backs | 98 | 64 | $102,819,999 | $1.049 |

| Cleveland Indians | 74 | 88 | $78,909,449 | $1.066 |

| Chicago Cubs | 67 | 95 | $75,690,833 | $1.130 |

| Boston Red Sox | 93 | 69 | $108,366,060 | $1.165 |

| New York Yankees | 103 | 58 | $125,928,583 | $1.223 |

| New York Mets | 75 | 86 | $94,633,593 | $1.262 |

| Texas Rangers | 72 | 90 | $105,726,122 | $1.468 |

Their new approach threw out many pieces of conventional baseball wisdom: stealing bases and bunting were strict no-no's, for example. Naturally, these changes brought about some tension, and it's this tension that makes for the dramatic thrust of the film. In particular, mathematics takes a backseat, though there are some little cameos for those who are paying attention.

The most significant piece of mathematics making an appearance in the film is the Pythagorean Expectation, a formula discovered by Bill James that estimates a team's win percentage in terms of its runs scored and runs allowed. More specifically, the formula asserts that a team's win percentage is approximately equal to

For example, the 2002 A's scored a total of 800 runs, and allowed a total of 654 runs, for a Pythagorean Expectation of

(relevant stats can be found here). This compares to the team's actual win percentage of 103/162, which is around 0.636.

In the film, Peter Brand applies this formula in order to estimate the number of runs the team needs to score, along with the maximum number of runs it can allow, in order to secure a playoff spot. In one scene, he tells Billy Beane that he thinks the A's will need to win at least 99 games to guarantee a playoff spot. In a 162 game season, this equates to a win percentage of around 0.611. In order to ensure that the Pythagorean Expectation is at least this large, we set

With a little algebra, this is the same as

Brand then informs Beane that in order for this to happen, the team needs to score at least 814 runs, and can allow no more than 645 runs. This gives a runs allowed to runs scored ratio of 645/814, or around 0.793 < 0.798 (though, if I were being anal, I would point out that with 814 runs scored, the team could allow as many as 649 runs and still have a runs scored to runs allowed to runs scored ratio that is less than 0.798).

While the math formulas on display in the film are accurate, I would be remiss if I did not briefly discuss Hill's portrayal of Peter Brand. Overall, Hill does a good job; though Brand is clearly a nerd, Hill's portrayal usually avoids caricature.

Like every other film featuring characters who are good at math, though, Moneyball can't help itself from including a scene where we see how good Brand is at math because he can do mental calculations quickly. This particular scene takes place when Brand is sitting in his first meeting with Beane and the rest of the baseball scouts, and though it serves to highlight the tension that exists between Brand's new school of thought and more traditional baseball thinking, I think the scene could have been just as effective without the clichéd math exercise.

Also, in the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that there are some who feel the story told in Moneyball (both the film and the book) is an exaggeration. More specifically, as this Slate article discusses, many people believe that the reason for the A's success during the early aughts had less to do with sabermetrics, and more to do with the fact that they had awesome pitchers in Tim Hudson, Mark Mulder, and Barry Zito, none of whom feature prominently in the book or film. While I don't feel knowledgeable enough to weigh in decisively on this issue, the role of the defense certainly appears to be underrepresented here.

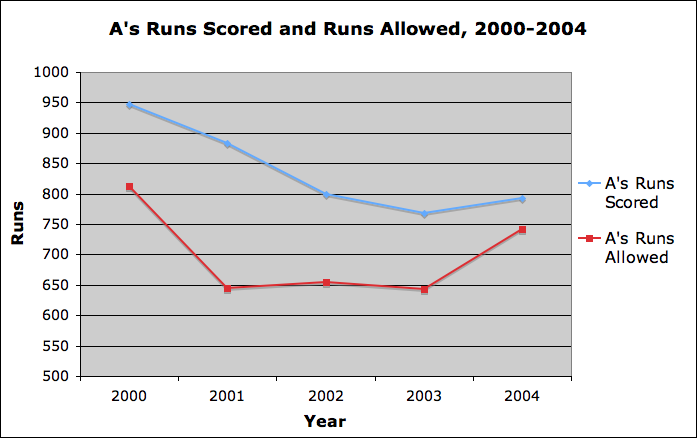

To try and convince you of this, recall that the A's made it to the playoffs in four consecutive years, from 2000-2003. Here is some data on how many runs they scored and how many runs they allowed during each of those years, and in 2004, when they did not make the playoffs:

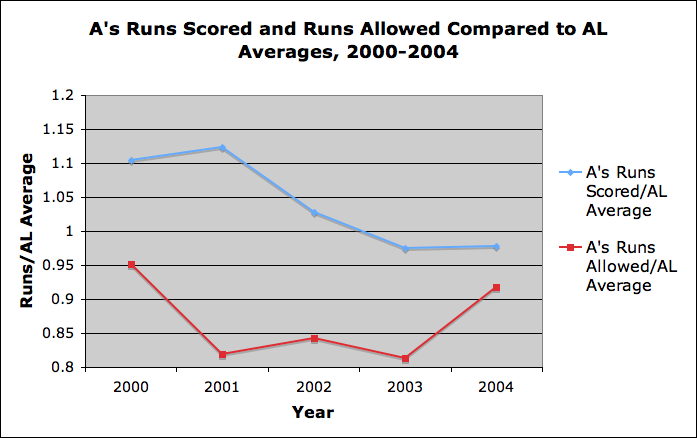

Observe that especially from 2001-2003, while the A's offense declined, their defense remained consistent in allowing relatively few runs. Of course, this should not be viewed in a vacuum, but rather in relation to how baseball as a whole performed. Therefore, it is better to consider not runs scored and runs allowed, but runs scored and runs allowed as a proportion of runs scored and runs allowed in the American League. With this slight adjustment, we get the following picture:

Note in the above that a proportion of 1 means that the A's were performing at an average rate, while a proportion greater than 1 indicates above-average performance, and a proportion less than 1 indicates below-average performance. As we can see from the data, in 2001-2003, the A's defense was allowing runs at a rate well below the average; in other words, the defense was relatively strong. On the other hand, during the same period, the offense consistently weakened year-over-year, so that the number of runs the A's scored was below the league average in 2003-2004. In particular, during the 2002 season profiled in Moneyball, the number of runs scored took a sharp downturn relative to the league average, while the number of runs allowed still remained well below average. This indicates, to me at least, that the role of the defense was certainly an important factor in the A's playoff runs during the 2002 and 2003 seasons. Note also that in the 2004 season the number of runs allowed rose sharply relative to the league average; without a corresponding uptick in runs scored, the A's didn't make it to the playoffs.

Nevertheless, I don't think the issue is binary; excellent pitching and a sabermetric approach probably combined to help the A's. Even though Moneyball only explores one of these issues, it's still a film well worth seeing. If you're no fan of mathematics, don't worry, there isn't much on display. And if you're no fan of baseball, surprisingly, I think you might enjoy the movie anyway.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus