Test Taking, Part 3

If you'll permit me this small indulgence, gentle reader, this week I'd like to return to a topic from last month. More precisely, I'd like to continue the series of posts that discussed how one best ought to prepare for an exam in which all N questions are given beforehand, and one knows that M questions will appear on the exam, of which the student must answer K. In my first post I discussed this problem in the context of preparing essays, while in my second I discussed it in the context of preparing for the US citizenship exam.

Apparently I'm not the only one who thought this a worthwhile problem. This problem has also made an appearance at the fun-filled blog Mind Your Decisions (it's an excellent discussion, so if this kind of thing suits you, check it out). In the comments section, discussion on this problem continues; in particular, one person proposed that the model should be modified to include the possibility of guessing. This is an entirely reasonable thing to want, and thankfully it can be incorporated into the model without too much added effort.

Let me recall the notations I used when I discussed the problem earlier. I've already mentioned N, M, and K. Let's let n represent the number of questions you can answer, and of those n, let X represent the number that actually appear on the exam. As we've seen, X satisfies a hypergeometric distribution, and the probability that X is some value k is given by

P(X=k)=(MN)(kn)(M−kN−n).

Moreover, since you will pass the exam only if X is at least K (in other words, only if the number of questions on the exam that you can answer is at least the minimum number of correct answers need to pass), the probability of passing is

P(X≥K)=(MN)−1k=K∑min{M,n}(kn)(M−kN−n).

This is all review from the earlier posts, and does not take into account the effect of guessing. Let us now imagine how we can include this refinement into the model.

Intuitively, if we are allowed to guess, then the probability of our being able to pass should increase. To make things as simple as possible, let's assume that if you don't know the answer to a question, you have a probability p of guessing correctly - in other words, the probability of a correct answer is the same for each question. Let's also assume that the probability of guessing correctly is independent of the number of questions on the exam that you can answer without guessing (we'll use this assumption in a moment).

In this modified situation, you will win if you can answer enough questions, or if you can guess enough correct answers in the event that you can't answer the minimum number of questions with absolute certainty. So, if X is at least K, nothing changes - you'll simply answer the minimum number of questions and call it a day. What's new is the situation when X < K, in which case you'll need to guess in order to try and pass.

Roughly speaking, then, the probability of passing is equal to P(X ≥ K) + P(X < K and you guess correctly enough times). How many times is "enough"? Well, X plus the number of correct guesses must be at least K. Considering the cases X = 0, 1, ..., K - 1 separately, we can rewrite this as

P(X≥K)+i=0∑K−1P(of the other M−i questions correctlyX=i and you guess at least K−i).

Since the value of X is independent of the number of correct guesses you'll make, this can be written as

P(X≥K)+i=0∑K−1P(X=i)P( of the other M−i questions correctlyyou guess at least K−i).

Moreover, since we want the number of correct guesses to be between K - i and M - i, we can write the above as

P(X≥K)+i=0∑K−1P(X=i)j=K−i∑M−iP(j correct guesses out of M−i).

Now, the probability occurring in the sum over j should hopefully look familiar to anyone with a basic background in probability. The number of successes out of a fixed number of trials given that the probability of success is some number p follows the Binomial distribution, one of the first probability distributions encountered in any course in probability or statistics. In particular, since we've said that the probability of a correct guess is p, knowledge of the binomial distribution tells us that

P(j correct guesses out of M−i)=(jM−i)pj(1−p)M−i−j.

In summary, the probability of passing is

P(X≥K)+i=0∑K−1P(X=i)j=K−i∑M−i(jM−i)pj(1−p)M−i−j.

If we want a more explicit formula, we can also use our knowledge of the probability distribution for X. Also, notice that P(X = i) is 0 if n < i (the number of questions on the exam for which you know the answer can't exceed the number of questions in total for which you know the answer), so we can write the probability of success in two ways, depending on whether n < K or n ≥ K.

If n < K, then the probability of passing becomes

(MN)−1i=0∑n(in)(M−iN−n)j=K−i∑M−i(jM−i)pj(1−p)M−i−j.

In the case that n ≥ K, we have a contribution from the P(X ≥ K) term, and so the total probability is

(MN)−1k=K∑min(M,n)(kn)(M−kN−n)+(MN)−1i=0∑K−1(in)(M−iN−n)j=K−i∑M−i(jM−i)pj(1−p)M−i−j.

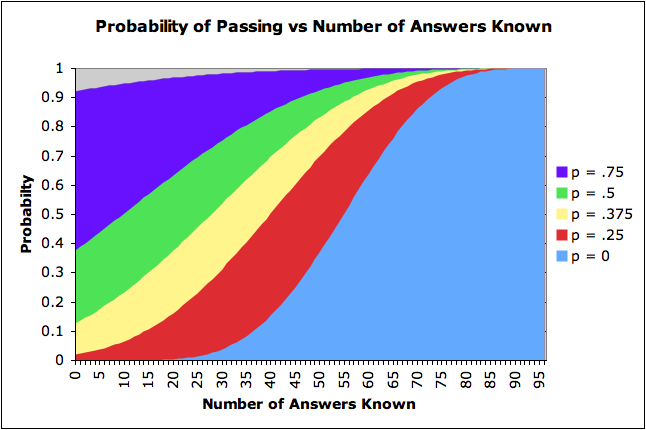

This is all well and good (and agrees with what commenter Scott derived in the comments of the Mind Your Decisions post), but what does it say about our example from last time (where N = 100, M = 10 and K = 6)? As before, here are some graphs of the probability of success as a function of how many questions you can answer. Note that any such graph depends on the probability p. So, let's illustrate two examples:

Case 1: p is a fixed value. Here are the graphs corresponding to p = 0, p = .25, p = .375, p = .5, and p = .75 (i.e. the chances of you guessing correctly are either 25%, 37.5% 50%, or 75% - note that the case of p = 0 corresponds to the previous case where guessing isn't a factor).

Some highlights — without guessing, you need to know the answers to 55 questions in order to have at least 50% chance of passing. With a 25% chance of guessing correctly, you only need to know the answers to 40 questions. At 37.5%, the number of questions decreases to 28, at 50% it drops to 10 questions, and if you have a 75% chance of answering correctly, you have over a 90% chance of passing without knowing any answers at all! If you want at least an 80% chance of passing, the number of answers becomes 67 (p = 0), 56 (p = .25), 48 (p = .375), and 35 (p = 0.5).

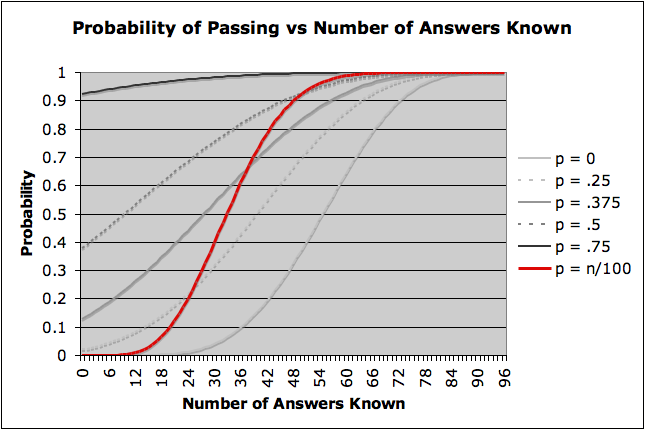

Case 2: p increases with n. It seems reasonable to assume that the more answers you know, the better your chances of correctly guessing the answer to a question you don't know, since you will be more knowledgeable in general. In this particular example, I've taken p to equal n/N (in this case n/100). Note that with this choice, initially the probability of success will be 0, but as n grows the probability of success should grow relatively rapidly.

The above graph quantifies the above heuristics. Note that the red line grows very rapidly, so that the probability of success is greater than 50% after memorizing 33 questions, more than 80% after 43 questions, and over 95% after slightly over half of the questions (53).

So there you have it. If you are feeling lazy the next time you have to prepare for an exam, hopefully this will provide you some guidance as to the minimum amount of work you can do while still being reasonably confident that you won't fail.

Hope you all have a great weekend!

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!