Addendum to Math Gets Around: The Humanities

Last week we discussed an example of when a mathematical background might prove useful even in the least quantitative of liberal arts courses. More specifically, we asked the question: if a teacher gives you a list of N questions, tells you that M will be on an exam, and you must answer K of the questions given on the exam, what's the minimum number of questions you should prepare to guarantee that you will be able to answer K of the questions on the exam? (Answer: N + K – M.) We also looked at the question probabilistically - namely, we saw that of the questions appearing on the exam, the number that you've prepared for follows a hypergeometric distribution.

As a concrete example I considered the case N = 6, M = 5, K = 3 - in this case, the minimum number of questions you should prepare to guarantee that you can answer 3 of 5 problems on the exam is 4, and we saw that if you only prepare 3 questions, you have a 50% chance of those 3 questions appearing on the list of 5.

Late last week, however, I was made aware of another example, one for which the probabilities might prove more interesting (since there are more cases to consider). Specifically, let us consider the case of a person studying to become a U.S. citizen. As part of this process, one must submit to an interview in which one is asked 10 questions, and must answer 6 of those 10 questions correctly. However, the potential list of questions is made available to people beforehand; there are 100 questions from which the 10 questions can be drawn. In other words, we have N = 100, M = 10, and K = 6.

In this case, to guarantee that you will be able to answer 6 of the 10 questions presented, our analysis from last time tells you that you should prepare 100 + 6 – 10 = 96 of the questions. Indeed, this makes sense, since the worst that can happen is that the 4 questions you don't prepare happen to be precisely 4 of the 10 questions you are asked in the interview. This also reflects the fact that the closer M is to K, the more questions the test taker will have to prepare (note that if M were closer to N, say M = 90, the test taker would only have to prepare 16 questions).

Still, preparing 96 of the questions may seem like a little much, especially since only 10 questions will come up in the interview. So, let's see what happens if someone prepares for fewer than 96 questions. Obviously one should know how to answer at least 6 of the questions, but what about values between 6 and 96?

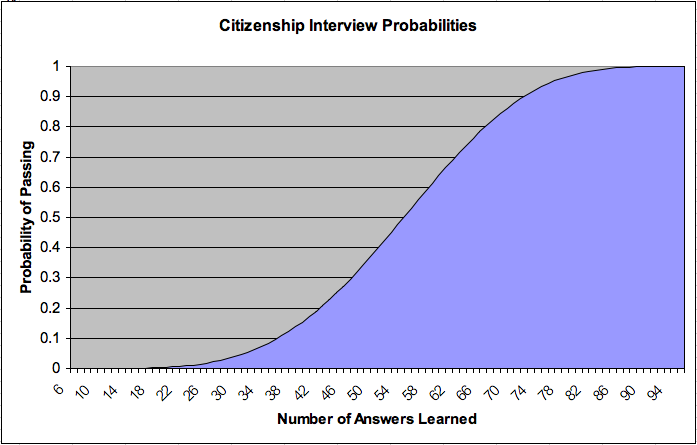

Here is a graph showing the probability that one will pass the interview given that one has learned the answer to n questions, for some n between 6 and 96.

This graph tells you that, for example, even if one only had time to learn the answers to 73 out of the 100 questions, one's chances of passing the exam would still be over 90%. Those are pretty good odds, for only learning the answers to roughly three quarters of the questions. On the other hand, one needs to learn the answers to 37 questions before one's odds of passing rise above 10%, so it's certainly not likely that someone will pass by learning the answers to only a handful of questions (which is probably what the government intends).

If only Apu had known of these findings, perhaps he could have saved himself some trouble.

Anyway, I just wanted to highlight another example where these ideas apply. If you can think of any others, let me know! Also, if you are interested in the content of the 100 questions that can be asked of our future citizens, you can find the full list (along with acceptable answers) here.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!