Jack Doesn't Know Jack

Late last month, HBO films premiered You Don't Know Jack, a biopic on assisted suicide advocate Jack Kevorkian. The casting of Al Pacino in the starring role turned out surprisingly well, and made for a film that was better than I had expected.

However, no film is perfect, and You Don't Know Jack has its share of faults. Unlike most films, though, one of You Don't Know Jack's problems falls into the realm of the mathematical.

As you may recall, Kevorkian escaped conviction for his assisted suicides a number of times. The film's reasoning for his acquittals is a mixture of good legal representation combined with heart-wrenching testimony from the families of the deceased, who made it clear how much suffering Kevorkian's patients endured before he helped them. Moreover, Kevorkian never administered any lethal injections himself; instead, he built mechanisms that his patients could activate themselves.

Kevorkian pressed his luck in the late 90s, however, when he allowed footage of an assisted suicide to be broadcast on 60 Minutes along with an interview explaining that he wanted to move the public debate from assisted suicide to euthanasia. As expected, Kevorkian was arrested, but perhaps to his surprise, this time around he was convicted as well.

This is a clip from the infamous 60 Minutes episode. Viewer beware, the video doesn't exactly make for easy watching.

Contributing to his conviction, according to the film, was the fact that Kevorkian represented himself at the trial. Moreover, because prosecutors went for a murder conviction instead of an assisted suicide conviction, testimony from the family was not allowed to be heard by the jury. This lack of evidence for Kevorkian's defense undoubtedly hurt him. However, one can't help but feel that his mathematical background hurt him as well.

Let me explain. At one point in the trial that would send him to prison, Kevorkian is questioning the doctor who performed the autopsy on Kevorkian's patient. The following conversation ensues:

Kevorkian: Is homicide always murder, doctor?Dr. Dragovic: No, sir.Kevorkian: When is it not murder?Prosecutor John Skrzynski: Objection. That's a legal question.Judge Jessica Cooper: Sir, you may question him in regard to his autopsy report, but nothing further that's legal.Kevorkian: Why?Cooper: If you'd consult with your attorney, he'd tell you why.Kevorkian: Uh...ok. Is euthanasia always murder?Attorney: Objection.Kevorkian: Always homicide?Dragovic: Yes, sir.Kevorkian: Yes, it's always homicide. And you stated that homicide is not necessarily always murder. Therefore, out of pure logic, wouldn't you say that euthanasia is not always murder?Attorney: Objection, calls for a legal conclusion.Kevorkian: No, calls for simple logic, it's a, it's, it's, it's, it's a syllogism, it calls for nothing but syllogism.Cooper: Again, you're asking him to make a legal conclusion.Kevorkian: No, but this is a mathematical conclusion. It's simple arithmetic!

Simple thought it may appear, Kevorkian here has made a fallacious argument. Let's try to pinpoint the problem.

The above syllogism consists of two premises and one conclusion:

- Premise 1: Euthanasia is always homicide.

- Premise 2: Homicide is not always murder.

- Conclusion: Euthanasia is not always murder.

What's wrong with this conclusion? Abstracting further, we see that the basic argument is of the form "All A is B, and B is not always C, therefore A is not always C." Some thought should leave you skeptical as to the truth of this statement. For example, suppose we consider the following argument:

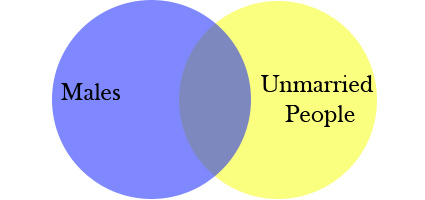

- Premise 1: Bachelors are always unmarried.

- Premise 2: People who are unmarried are not always male.

- Conclusion: Bachelors are not always male.

Of course, we know the conclusion in this case to be false, but the argument is exactly the same as the one Kevorkian used.

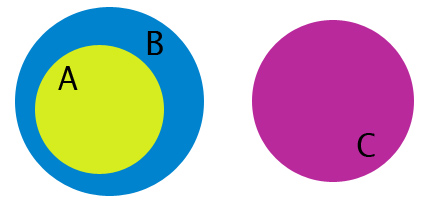

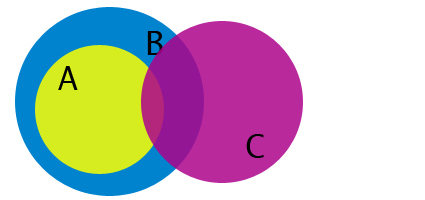

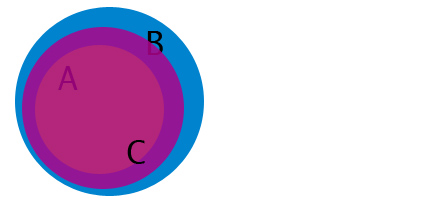

To get an idea of what's going on here, some Venn diagrams may be helpful. If we return to our friendly letters A, B, and C, then the first premise tells us that A is contained in B, and the second premise tells us that B is not contained in C. However, these two facts alone do not tell us anything about the relationship of A and C. These Venn diagrams all represent situations in which the first two premises are true:

In the first picture, we see that B and C are disjoint; not only is B not always C, but it is NEVER C. In this case, Kevorkian's argument would hold true.

It would also hold true in the second picture. This time we see that C intersects both A and B, but still, there are times when A is not C.

In the third picture, however, the premises still hold (A is always B, B is not always C), but the conclusion fails, because A, in addition to being contained in B, is also contained in C. This is what happens in the bachelors example: in this case, bachelors make up the intersection of males and unmarried people, and is therefore contained in both larger sets:

I don't know whether or not Kevorkian committed this deductive fallacy at has actual trial, or whether this scene was a product of the writer's imagination. Either way, the movie shows that Kevorkian's lack of knowledge on the law certainly was a detriment to his defense. I'm simply trying to show that his lack of mathematical knowledge wasn't helpful either.

Even so, the movie's worth watching. In closing, please enjoy the following trailer.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus