More on Football Pools

Update: Part 3 of this series of posts can now be found here.

This post is a follow-up to an earlier post that looked at betting squares for football scores. In particular, we analyzed the distribution of the second digit of final football scores, and compared that to the digital root of final football scores (recall that the digital root of a number is found by iteratively calculating the sum of the digits in that number until you come up with a single digit number from 1 through 9). We found that on average, the final digits of football scores do not distribute themselves evenly - a score ending in 2 or 5 is much rarer than a score ending in 7 or 0, for example. However, the analysis of the digital root suggested that digital roots may become evenly distributed on average.

We now turn to a related question of independence, which was mentioned at the end of the previous post. More specifically, we address the following question: is the second digit of the home team's football score independent of the second digit of the away team's score? What if we replace "second digit" by "digital root" in the above question?

A more basic question that is related to both of these is whether or not the two final scores in a football game are independent. The answer to this question is not entirely obvious. On the one hand, knowing that one team scored 7 points doesn't tell you anything a priori about the second team's score. On the other hand, one team's score during a game will certainly influence the strategy of the opposing team: if one team is ahead by a wide margin, for example, the losing team will likely play riskier in the hopes of making some big plays. Conversely, if the difference in scores is very close, teams are less likely to make plays that are as risky unless it's late in the fourth quarter.

Alternatively, what if you are told that one team scored 7 points, but that the game went into overtime? Now you know a great deal about the other team's score: since overtime in the NFL is sudden death, and since the only way to score 7 points is by a touchdown or the (very unlikely) combination of a field goal and two safeties, you know that the other team must have scored 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, or 13 points.

From these examples, it seems that football scores aren't entirely independent - there is often some relationship between the two. However, it's natural to think that perhaps on average, we do have independence. Similarly, we may hope that by looking at several games, we have independence of the second digit or the digital root between home and away teams.

One reason to hope that we would have independence is that it allows us to calculate probabilities of winning squares with much less input. If the probability of the home team having a score that ends in a 7 is 17%, for example, and the probability of the away team having a score that ends in an 8 is 7%, we'd like to be able to say that the probability of the (7, 8) square winning in a football pool is .17 x .07. Otherwise, to estimate the probability of any particular square winning we'd have to rely on historical data, and create a running tally of how each square has performed. Needless to say, this is more work.

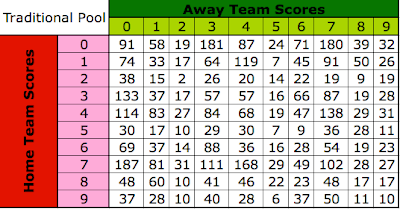

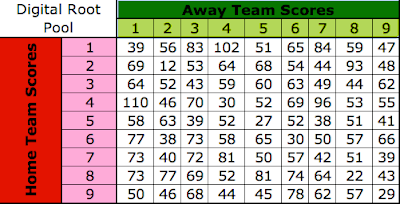

Unfortunately, it seems that this is necessary work. By looking at data from 4,642 preseason and regular season games from 1994-2008 (the 1994 season was the first in which the two-point conversion was instituted), I tallied the counts for each winning square in the case of both the traditional football pool and the digital root pool. Here is the data:

Recall that for the digital root pool, the digit 0 only occurs if one team doesn't score - to even things out, I have assigned a score of 0 with a digital root of 9 (I discussed reasons for this in my earlier post).

Using a standard statistical test for independence, we conclude that there is essentially no way that the digital root of one team is independent of another team, or that the last digit of one team's score is independent of another team's score.1 To illustrate one example, 10.8% of the home team's scores had a digital root of 2, while 9.26% of the away team's scores had a digital root of 2. Therefore, assuming the digital roots of the away team and home team's scores were independent, the probability of winding up in the (2,2) square would be 0.108 x 0.0926, which is approximately 1%.

However, as the data shows, only 12 games ended in the (2,2) square this gives a much smaller probability of 12/4,642, which is approximately 0.26%. In other words, if you know that the score of the home team's digital root is 2, it is suddenly much less likely that the score of the away team's digital root is also 2.

Some other observations:

Using this larger data set, we also find that it's actually unlikely that the digital roots become equally distributed among the digits from 1 to 9. While the distribution is certainly more uniform than in the case of the second digit, we also see that certain digital roots occur significantly more frequently than others (5 occurs much less frequently than 1, for example).

Even though away team and home team 2nd digits and digital roots are not independent, one may expect that the probability of having a score with a given 2nd digit or a given digital root should be independent of whether the team is the home team or the away team. Interestingly, in the case of the 2nd digit, this is not true. In particular, it is more likely for an away team's score to end in a 3 than a home team's score, and it is more likely for a home team's score to end in an 8 than an away team's score.2 In the case of the digital root, however, the data is insufficient for us to reject the hypothesis that the probability that the away team's score has a certain digital root should be different from the probability that the home team's score has a certain digital root.3

In considering the relative merits of the traditional football pool versus the digital root method, one question from my earlier post remains unanswered: which method will hit the most squares during a typical football game? It seems reasonable to expect that the digital root method will hit a larger number of squares than the traditional method. For example, if the score is 13-7, and the home team scores a field goal followed by a touchdown, two boxes will be hit by the traditional pool: (3,7), (3,0), followed again by (3,7). However, the digital root method will hit three boxes: (3,7), (3,1), and then (3,8).

This heuristic is certainly reasonable, but does it hold when looking over a large number of games? I'll return to this question in a later post.

In the case of the last digit, we obtain a χ2 value of 425.50 with 81 degrees of freedom, which gives a probability that is essentially 0. Similarly, in the case of the digital root, we obtain a χ2 value of 326.52 with 64 degrees of freedom, again yielding a probability that is essentially 0.

Testing the Null Hypothesis that the probability that a home team's score ends in a 3 is equal to the probability that the probability that an away team's score ends in a 3 yields a χ2 value of 33.62 with 1 degree of freedom. Replacing 3 with 8 gives a χ2 value of 11.86. At a 0.01 significance level and 1 degree of freedom, we reject the null hypothesis if χ2 is larger than 6.6348.

In other words, the χ2 values in the digital root case are never larger than 6.6348. The case of the digital root equal to 5, however, comes close - in this case, the χ2 value is 6.6130.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus