Math Gets Around: On Birthdays and Trading Cards

Today marks the 1 year anniversary of Math Goes Pop! I started on somewhat of a whim after reading an article about compulsory Algebra I education for all California 8th graders (although what with our finances down the toilet, who knows what the current status is here). When I started writing I wasn't sure there was enough content out there to sustain a blog with this one's focus. Once I started digging, though, I found that the rabbit hole went quite deep, and so here I am a year later with plenty left to talk about (the recent obsession with pointless math holidays certainly has helped with my output).

Given the date, it seems fitting to begin by mentioning the birthday problem. This is a standard problem given in any introductory probability course, but many people find the result counter intuitive at first.

The birthday problem asks a simple question: if you have a room full of people, how many people do you need so that there's a 50% probability that at least two of them share the same birthday? In the simplest setting, we make a few assumptions: for example, we usually ignore the presence of leap years, and we assume that each day of the year is equally likely to be someone's birthday.

With these assumptions, solving the problem is not difficult. The probability that at least 2 people in a group of n share a birthday is 1 minus the probability that all n people have different birthdays. In other words, the probability is

This is because the second person has a 1 - 1/365 = 364/365 chance of having a birthday different from the first person, the third person has a 363/365 chance of having a birthday different from the first two people, and so on.

So, to answer the question, we just need to find the smallest n such that the expression above is greater than 1/2. The punchline is that n only needs to be 23 or more in order for this inequality to hold. In other words, in any room with at least 23 people, there's a better than 50% chance that two of them have the same birthday.

For many people, this number seems too low - after all, you may have been in several groups of 23 or more and never or rarely met someone with your birthday. The problem with this argument is that it addresses a different question. The reason why we only need 23 people to have a 50% chance of finding a common birthday is that we are placing no restriction on the date of the shared birthday. Requiring that someone share the same birthday as you fixes the date, and this changes the problem.

If instead you want to know how many people you need in a room so that there's a 50% chance one of them will have the same birthday as you, this probability is given by the new expression

To make this greater than 1/2, we need to take a much larger n: n = 253, to be precise.

As I said, this is a well-known problem in probability theory. A few months ago, however, I was asked about a variant of the birthday problem by my friend Gabe over at Motivated Grammar. Rather than looking for identical birthdays, what if you look for different birthdays? More specifically, how many people do you need in a room to guarantee with, say, a 90% certainty, that every day of the year is someone's birthday?

Of course, you could always pick poorly so that everyone in the room has the same birthday, but the odds of this happening are quite low. In fact, this problem is more commonly known by another name: the coupon collector's problem.

For this problem, suppose you are clipping coupons from a newspaper (any newspaper except for USA Today). There are n different coupons you can collect, but each newspaper only has 1 coupon, and you can't see which coupon the newspaper has until you've bought the newspaper. In this context, the question becomes: what's the probability that you'll need to buy at least newspapers to collect n coupons?

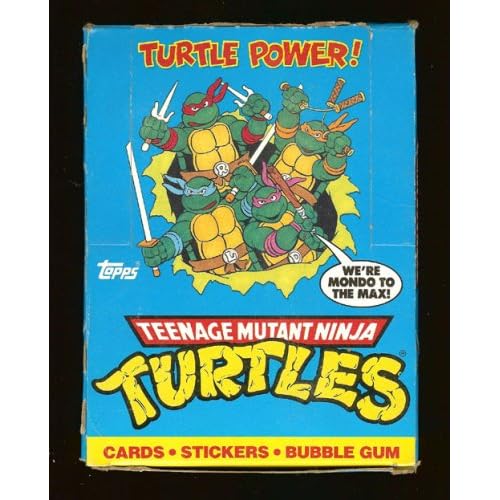

If you prefer, you can think about this problem in terms of trading cards as well. Each pack of cards is akin to buying a set of newspapers, and you want to know the probability that you'll need to buy at least a certain number of packs in order to collect all the cards. From baseball players to Pokemon, this same problem governs the distribution (assuming that all cards in the back are equally likely to be in the pack, which may not always be the case).

What's known about this problem? Well, as I said above, even if you buy hundreds of thousands of cards, or stuff millions of people in a room, there's no guarantee that you'll collect every card or every date. However, on average, the number of cards you'll need to go through to complete a set of size n is about n*logn.

In terms of birthdays, this says that if you want to collect every date, on average you'll need to pool together around 2,153 people. Why such a large number? It's not unreasonable to expect something like this - when you first begin collecting people, it won't be hard to get people with different birthdays. However, as your numbers increase, you'll get a new birthday less and less frequently. Finding that last birthday could prove to be quite elusive.

The same analysis works for trading cards. Trying to complete your collection of series 2 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Animated Series trading cards? Well, my friend, with 88 cards total and 5 cards per pack, you can expect to buy around 79 packs of cards. Perhaps this box set would be a better investment.

While the expected values are easy to calculate, it may be that you need to greatly exceed the expected value in order to complete your collection. However, one can use Markov inequalities to get bounds on the probabilities. For example, there's a 90% chance that you'll be able to hit every birthday if you take no more than about 21,535 people. To bump those odds up to 95%, take 43,069 people.

So, for parents whose children who have gotta catch 'em all, you can use these methods to get a rough estimate for how much that completion will cost you. And if you're trying to get a room full of people together so that every day of the year is someone's birthday, I'd strongly suggest not picking people at random. What an awkward party that would be.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus