Wedding Mathematics, Part 3

Today I would like to wrap up my series on mathematics and weddings (a series begun here and continued here) with a little advice for soon-to-be brides and grooms who are looking to integrate some math into their celebrations. If this describes you, then congratulations - not only on your upcoming nuptials, but also on the classy way you are looking to celebrate them.

For our own wedding, my bride and I decided it would be natural to incorporate some mathematics into the table numbers. There is some freedom in how one decides to do this. For example, we initially toyed with the idea of using numbers for the tables that were somehow significant to us and our relationship, but found it too difficult to come up with examples meeting this criterion. If one wants intrinsically interesting numbers, there are many examples among the whole numbers (I was particularly fond of using the smallest whole number expressible as the sum of cubes in two different ways). In the end, though, we decided to expand the realm of p0ssibilities beyond the range of whole numbers. This turned out to be a good decision, both aesthetically and educationally.

Table number e. Hat tip to Caroline for the shot.

If you are looking for a way to incorporate some math into your celebration, the table numbers are certainly one option. At each of our tables we had a small placard, with the number on one side and a brief description of the number (and some table exercises!) on the reverse. I tried to have sympathy for our audience, and give descriptions that a general audience would be able to understand, though I gave myself more flexibility with a table occupied by other math students. For sake of completeness, here are all the numbers we used, along with their descriptions (see if you can tell which table had the math students!). In no particular order:

1. π (see here for more).

The ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, π is perhaps the most famous irrational number. Historically, π has also been known as Archimedes' constant, and Archimedes himself proved that .

More than one trillion digits of the decimal expansion of π have been computed, and folks with nothing better to do than recite those digits come together each π day (March 14th, naturally) to see who has memorized the longest string of numbers in the decimal expansion. If you're looking for more interesting properties of π, though, here are a few to mull over:

Table exercises!

Use geometry to show that . These bounds are not as good as those of Archimedes, but they are easier to derive.

(Harder!) Explain why π is irrational, i.e. why it cannot be written as a fraction p/q where p and q are integers.

2. e (see here for more).

e, a.k.a. Euler's number, a.k.a. Napier's Constant, is an irrational number of fundamental importance. While it lacks the general public awareness of a number like π, I assure you it is no less charming. Typically defined as the limit

e enjoys many other identities, including

and

e also determines the base of the exponential function ex, unique among all exponential functions in the study of calculus because it is equal to its own derivative.

Table exercises!

Use one of the identities above to verify that e < 3.

Use one of the identities above to verify that e is irrational, i.e. that it cannot be written as a ratio p/q where p and q are integers.

Suppose each of you has brought a hat to this wedding. Everyone leaves his or her hat inside, and when a person leaves, he can't be bothered to search for the hat he brought, and simply takes one from the hat pile at random. Show that the probability nobody ends up with the hat they came in with tends to 1/e as the number of people increases.

3. ζ(3) (see here for more).

Take all the perfect cubes (13 = 1, 23 = 8, 33 = 27, and so on), take the reciprocals of all those perfect cubes, and add them all together. You will end up with a number that is sometimes called Apéry's constant, and is written

The constant is named in honor of Roger Apéry, who proved in 1978 that this number is irrational. Intuitively, one can interpret 1/ζ(3) as the probability that three randomly chosen whole numbers will have no prime factors in common.

One can consider more general numbers as well. For example, for any whole number k bigger than 1, the sum

will yield some finite value. When k is even, one has nice formulas for the values, for instance ζ(2) = π2/6, ζ(4) = π4/90.

In fact, it is possible to let k take on quite a large range of values. The function one gets is called the Riemann zeta function, and lies at the center of one of the most famous unsolved problems in mathematics.

Table exercises!

Show that ζ(1) = ∞.

Given that ζ(2) = π2/6, show that 1 + 1/32 + 1/52 + 1/72 + ... = π2/8.

4. γ (see here for more).

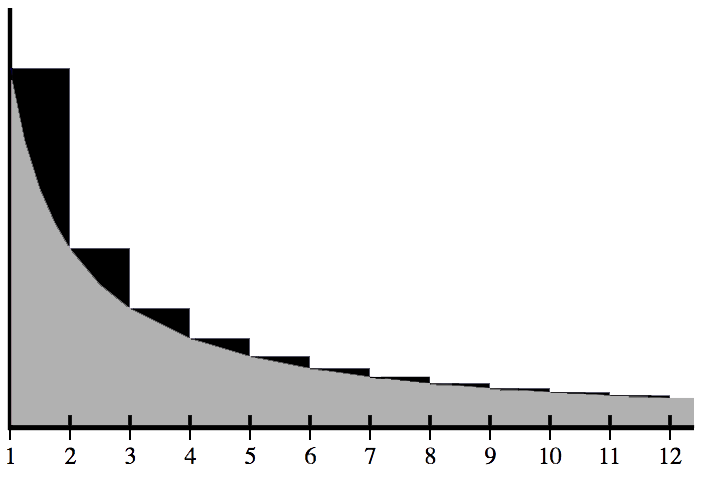

γ, a.k.a. the Euler-Mascheroni constant (not to be confused with Euler's number e), is perhaps best introduced geometrically. Consider the following figure:

The black portion of the area pictured above is found by drawing rectangles between two integers n and n + 1 with height 1/n (the rectangle between 1 and 2 has height 1, the rectangle between 2 and 3 has height 1/2, and so on), and subtracting the area under the graph of the function y = 1/x. The total black area, if this picture were to be extented out to infinity, would represent the number γ.

γ can be approximated by its decimal expansion, γ ≈ 0.5772, and while this number comes up quite naturally in number theory and statistics, surprisingly little is known about it. For example, it is unknown whether or not γ is a rational number (unlike constants such as π or e, which are known to be irrational).

Table exercises!

Using geometry and the figure above, show that γ > 1/4 + 1/12 + 1/24 + 1/40 + ... .

Show that the sum on the right hand side of the inequality in the first exercise equals 1/2, so that γ > 1/2.

5. ∞ (see here for more).

∞ is a concept of central importance in mathematics, and ergo, a concept of central importance in all things. While the figure-eight symbol for infinity is known and loved by all, it was not introduced until the year 1655, though many ancient cultures grappled with the idea of the infinite.

Though ∞ may seem like a single idea, great minds have shown that not all infinities are created equal. For example, the mathematician Georg Cantor showed that even though there are infinitely many whole numbers, and there are infinitely many real numbers, there are (in a sense that can be made rigorous) infinitely many more real numbers than counting numbers.

On a related note, the love Matt and Meg feel for you all for standing with them on this day is undoubtedly infinite. How this compares to their love for one another, however, is a problem that has yet to be investigated.

Table exercises!

Show that there are infinitely many prime numbers.

How does the number of even integers compare to the number of integers? Are there more of one type of number?

Suppose a set is finite with N elements. Show that the set of subsets of the original set is finite with 2N elements.

6. φ (see here for more).

Suppose two line segments have length a and b, with a larger than b. If the ratio of a to b is the same as the ratio of a + b to b, this ratio is called the golden ratio, and is written φ. In other words,

This, in turn, implies that φ2 – φ – 1 = 0, or (by the quadratic formula)

The golden ratio has a rich history, both mathematically and artistically. It is also closely related to the Fibonacci sequence, the sequence of numbers whose first two terms are 0 and 1, and where all subsequent terms are found by adding the previous two terms. In other words, the sequence begins 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, .... If we let Fn denote the nth Fibonacci number (so F0 = 0, F7 = 13, and so on), then

Table exercises!

1. Show why the above limit formula for φ is true.

2. Show that

3. Show that for any n, F0 + F1 + F2 + ... + Fn = Fn + 2 - 1

7. Λ (see here for more).

The de Bruijn-Newman constant, the value of which is currently unknown, is intimately connected to the Riemann Hypothesis. There exists a class of functions Ht(x), one for each real number t. H0(x) is essentially the Riemann ξ function, and in particular, the Riemann Hypothesis is true if and only if H0(x) has only real zeros.

Here are some properties of the family of functions Ht(x):

Ht(x) has only real zeros for any t ≥ 1/2.

If Ht(x) has only real zeros, then for any s ≥ t, Hs(x) has only real zeros too.

There exists a real value t0 such that Ht0(x) has at least one non-real zero.

These properties combine to show the existence of a constant Λ, lying somewhere in the range – ∞ < Λ ≤ 1/2, such that Ht(x) has only real zeroes if and only if t ≥ Λ. This is how the de Bruijn-Newman constant is defined. Moreover, the Riemann Hypothesis is equivalent to the statement that Λ ≤ 0.

The current best estimates for Λ state that

–2.7 × 10-9 < Λ ≤ 1/2,

so if the Riemann Hypothesis is true, it is, in some sense, “just barely” true. In particular, it's possible that Λ=0, in which case you are really just sitting at the 0 table. But while your table may be marked as such, you should know that none of you are zeros in our hearts.

Table exercises!

1. Prove or disprove the Riemann Hypothesis.

8. i (see here for more).

i, more formally known as the square root of -1, is defined to be one of two solutions to the equation x2 = –1 (the other solution being -i).

While this might seem like an arbitrary construction, in the larger context of history, it makes perfect sense. Just as the whole numbers are perfectly good for solving basic counting problems, but may be insufficient for problems involving debts or losses (where negative numbers play a prominent role), or problems involving rates or ratios (where fractions take the spotlight), the extension of numbers to include i leads to a wide variety of applications. This include (but are not limited to) applications in electrical engineering, signal processing, and fluid dynamics.

i is also one of the key ingredients in Euler's identity, one of the most popular formulas in mathematics. This formula states that eiπ + 1 = 0, and is noted for its unification of five constants of fundamental importance in mathematics: e, π, i, 1 and 0.

Table exercises!

1. Show that in = 1 whenever n is divisible by 4.

2. Find all x satisfying the equation x4 – 1 = 0.

3. The set of complex numbers is defined as the set of all a + bi, where a and b are real numbers. 1 + i is a complex number, as is π-7i. Can you define an addition law on the set of complex numbers? A multiplication law?

9. ρ (see here for more).

The plastic constant ρ can be viewed as a cousin to the golden ratio φ (see the φ table for more information). Formally, ρ is equal to the real root of the equation x3 = x + 1. The value of ρ is

Just as the golden ratio is intimately related to the Fibonacci sequence, the plastic constant is related to a sequence known as the Padovan sequence. The first three numbers in the Padovan sequence are given by

P0 = P1 = P2 = 1

and the nth term is given by adding two earlier terms in the sequence:

Pn = Pn - 2 = Pn - 3.

For example, the first few terms in the sequence are given by 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, ....

One can similarly construct a sequence known as the Perrin sequence. This sequence is similar to the Padovan sequence, but in this case, the equations needed to get started are A0 = 3, A1 = 0, A2 = 2, An = An - 2 + An - 3. In either case,

Table exercises!

1. Show why the limit formulas given above are true.

2. Show that the first few terms of the Perrin sequence are 3, 0, 2, 3, 2, 5, 5, 7, 10, ....

3. Show that if p is a prime number, Ap is divisible by p.

10. (see here for more).

Along with π, is probably the most well known number on display here. While it may seem mundane, has an interesting mathematical history, notably because it was one of the first examples of an irrational number (i.e. a number that cannot be expressed as a fraction p/q where p and q are both integers). An early proof of this fact is attributed to the Greek thinker Hippasus, a follower of Pythagoras; legend has it that when he discovered was irrational, the result was so controversial that he was thrown out to sea by his colleagues and drowned.

These days, mathematics is (for the most part) less fraught with peril. The following elegant identities involving have been met with much less controversy:

Table exercises!

1. Prove that is irrational (make sure you are removed from any large bodies of water).

2. Try to prove the identities written above.

3. For which whole numbers m is a rational number?

Enjoy the table exercises!

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus