The Futurama Theorem

In case you missed it, Futurama was recently resurrected from beyond the television grave, and this summer it began airing new half-hour episodes on Comedy Central. Although it's never reached the height of popularity achieved by its older sibling, The Simpsons, Futurama nevertheless has its own share of dedicated fans. Many of those fans appreciate the differences between this show and The Simpsons, the most obvious of which is the former's futuristic setting and sci-fi influences.

The setting of the show naturally lends itself to math and science jokes, and in this department Futurama does not disappoint. Last week, however, they seriously stepped their game up a notch, by featuring the proof of an original mathematical result as a central feature in the plot of the story.

The mathematics evolves quite organically. In the show, Amy and Professor Farnsworth have created a mind-switching device, which can swap the minds of any two individuals. After a brief discussion, they decide it would be neat to swap their own brains:

| Futurama | Thursdays 10pm / 9c | |||

| The Mind-Switcher | ||||

|

||||

As you might expect, before long they decide they want to swap back. Unfortunately, due to the brain's natural immune response, they discover that once two people have switched minds once, they can never switch back (obviously). This raises a question: once two people have swapped minds, can they get back to their original bodies by means of a third party? Bender eagerly switches minds with Amy at this point, for reasons that aren't important here. Afterwards, though, Farnsworth and Amy have the following discussion:

Prof. Farnsworth (in Bender's body): Now then Amy, we'll simply switch bodies, and then we'll... no, I'd be back in my body, but then you and Bender would be switched. And the Amy and Bender bodies can't trade minds again, since they just did!

Amy (in Prof. Farnsworth's body): Oh no! Is it possible to get everyone back to normal using four or more bodies?

Prof. Farnsworth: I'm not sure. I'm afraid we need to use....MATH!

(dramatic music underscores this last point)

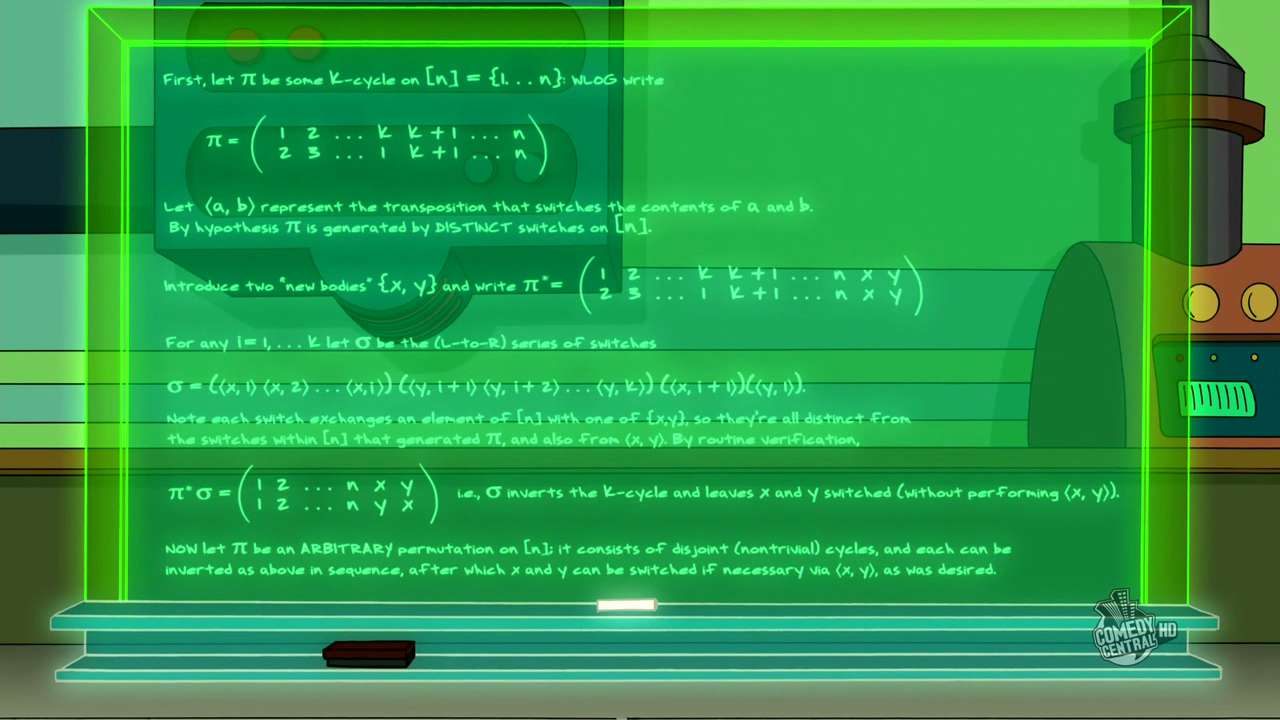

Throughout the rest of the episode, mind swapping occurs quite frequently. Amy (as the professor) swaps with Leela, Fry swaps with Dr. Zoidberg, Nikolai (the playboy ruler of the Robo-Hungarian empire) swaps with a bucket, and so on. By the episode's end, so much mind swapping has been going on that it's hard to keep track. Nevertheless, in the end it is discovered by 'Sweet' Clyde Dixon that by including no more than 2 new people in this mind swap game, everyone can always return to their original body. The proof is shown briefly, but for interested parties, here it is in all its glory (the proof was written up by writer Ken Keeler, who earned a Ph.D. in applied math from Harvard University):

The reader with some background will realize that this is a statement about the symmetric group on n elements (the notation used on the holographic chalk board is explained in the link). The gist of the argument is as follows: suppose that k people have swapped bodies. Label these people so that the 1st person is in the 2nd person's body, the 2nd person is in the 3rd person's body, and so on, so that the last person (a.k.a. the kth person) must be in the 1st person's body.

With two additional people (let's call them Xerxes and Yelena, or x and y for short) we can get everyone back to normal by using the following procedure: have the first body switch with y's body, then have the kth body switch with x's body. Next, have the kth body switch with y's body, and then, in turn, have x's body switch with the k - 1st body, k-2nd body, and so on, until x's body has switched with the 1st body. At the end of this procedure, everyone will be back to normal except for x and y, who will be in different bodies. But since they haven't switched with each other yet, they can then switch back.

I've omitted certain details that keep this from being a complete proof, but this is the heart of the idea (for more advanced readers, I have taken i = k - 1 in the episode's written argument). If the procedure seems confusing, let's take a particular example. Suppose that Professor Farnsworth and Amy knew of this theorem at the episode's opening: then they'd know they could switch back with the aid of two other people. Let's take Leela and Hermes as the other two players (since they seem to be the most responsible).

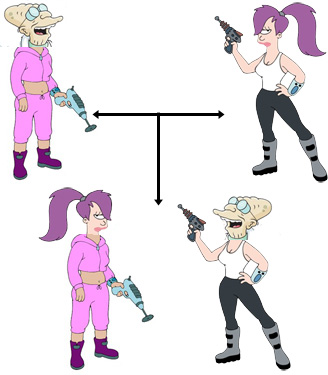

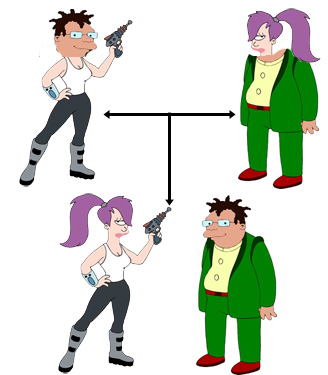

The theorem states that to get back to normal, first Amy's body and Leela's body should swap (the choice of Amy over Farnsworth or Leela over Hermes is arbitrary). Recall that Farnsworth is in Amy's body, so after the swap, he will be in Leela's body, while Leela will be in Amy's:

After that, Farnsworth's body and Hermes' body should swap. This gives the following picture:

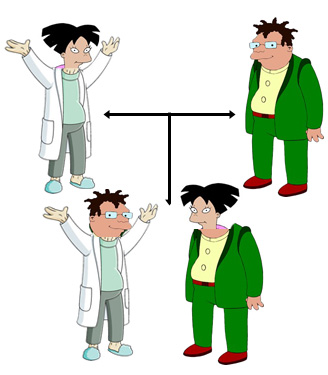

Now swap Leela's body and Farnsworth's body. Note that after this swap, Farnsworth's mind and his body have been reunited!

We can also reunite Amy with her body by swapping the bodies of Amy and Hermes:

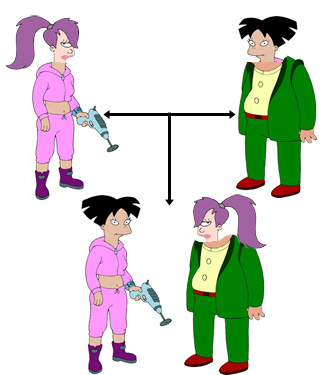

Now Leela is in Hermes' body and Hermes is in Leela's. But since they haven't swapped with each other at any point, we can now swap them with each other, thereby returning everyone to their original state!

This shows that we can get everyone back to their original state in only 5 moves. Moreover, each person only has their mind swapped 3 times.

This gives rise to several questions: in a group of n people, what is the minimum number of swaps needed to return everyone to normal? What is the maximum number? (The answer depends on the number of cycles in the permutation under consideration.) What is the maximum number of times an individual's mind must swap in order for the group to return to normal? If we place caps on this maximum (say, because the cerebral immune response gets stronger with repeated use), what restrictions does this place on how much fiddling with the mind swapping device before people won't be able to return to their bodies?

For this episode in particular, everyone returns to their bodies in 13 movies, although the speaker in the video below explains how that number can be reduced to 9.

If you are able to catch this episode when it airs again, I would highly encourage you to do so. Kudos to the writing staff of Futurama for not shying away from a bit of more advanced mathematics. While this result doesn't have far-reaching consequences, the fact that it is an original piece of work inspired by the plot of the episode is a great example of how critical thinking can be used to solve all types of problems.

In closing, I'd like to point out that I'm not the only person to have discussed this problem on the interweb. The video below offers a great explanation as well.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!