Martin Gardner and the Three Way Duel

As you may have heard, last week Martin Gardner celebrated his 95th birthday. Gardner, who authored the "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American for a quarter of a century, is often credited for introducing generations of young students to the beauty and charm inherent in mathematics. My favorite quote in this vein comes from professor Ron Graham, who is quoted in a recent New York Times article on Gardner as saying that "Martin has turned thousands of children into mathematicians, and thousands of mathematicians into children."

Both Scientific American and Wired ran articles on Gardner last week, and each one used a different expression to represent his age. Scientific American congratulated him on reaching an age of 25 × 3 - 1, while Wired proclaimed that Gardner had turned 5! - 25. Upon reflection I think I prefer the latter expression over the former, since the exclamation point in the factorial makes his birthday feel just a little more exciting. No matter your preference, however, I hope this encourages others to write their ages using mathematical expressions - more complicated expressions would be especially useful for ladies who don't wish to reveal their age.

In any event, I'd like to take the opportunity to celebrate Martin Gardner's birthday in my own way, by discussing a problem credited to him. There are a few variations on this problem, but all fall under the general name of the Truel. I first encountered this problem during a job interview, and the variant I heard then is the variant I'll discuss now.

Suppose there are three men: Mr. White, Mr. Gray, and Mr. Black. These three men have a score to settle, and so they decide to engage in a three way duel (or a "Truel," if you want to be cute). Mr. White is a rather poor marksman who hits his target only 1/3 of the time, In contrast, Mr. Gray is successful 2/3 of the time, and Mr. Black is an expert marksman who never misses. Because of this disparity, they agree that Mr. White shall shoot first, followed by Mr. Gray, followed by Mr. Black, and this sequential rotation shall continue until only one man remains standing.

Although Mr. White isn't so good with a gun, he is an expert strategist, and surmises that Mr. Black will dispose of Mr. Gray first, since Mr. Gray poses more of a threat than Mr. White. By the same reasoning, Mr. White assumes that Mr. Gray will shoot at Mr. Black before shooting at Mr. White.

Assuming that this analysis holds true, what should Mr. White do on his first turn to maximize the chance that he'll win?

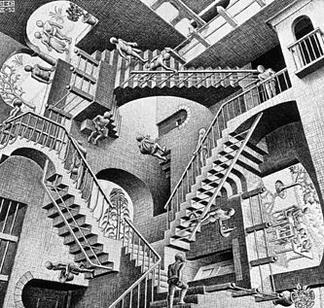

I'll discuss the answer below, but you should try this out for yourself if you've never seen this problem before. So that you don't peek at the answer accidentally, let's pause for a moment and look at some drawings courtesy of M.C. Escher.

So, what should Mr. White do? Should he shoot first at Mr. Gray or at Mr. Black?

Phrased this way, it's a bit of a trick question, since the answer is that Mr. White shouldn't shoot at either one. Instead, he should intentionally miss!

Intuitively, this seems reasonable if you reflect on it. The reason is that it's too risky for Mr. White to shoot at either of his opponents in the first round, because if he actually hits one of them, the remaining opponent will immediately turn and shoot at Mr. White. For example, if Mr. White shoots and hits Mr. Grey, he's done for, since Mr. Black will shoot at Mr. White and is guaranteed to hit. Similarly, if Mr. White hits Mr. Black, Mr. Grey will turn to shoot Mr. White. If, however, Mr. White shoots neither one, then either Mr. Black or Mr. Grey will be eliminated by the other one, leaving Mr. White with only one opponent to worry about.

For those looking for a more quantitative argument, we can use the odds given in the problem to calculate the probability that Mr. White will win if he a) shoots first at Mr. Black, b) shoots first at Mr. Gray, or c) shoots first at neither one.

As part of the analysis, we'll need to determine the odds that Mr. White will win when he's paired one-on-one against either one of his adversaries. For Mr. Black this is easy: if Mr. White faces off against Mr. Black, he has a 1/3 chance of winning, since if he misses Mr. Black will win with certainty.

In a face-off between Mr. White and Mr. Gray, however, things are more complicated. This is because there are many ways for Mr. White to win. He could win by hitting Mr. Gray on his first shot, he could win if both men miss and he hits Mr. Gray on his second shot, he could win if both men miss twice and he hits Mr. Gray on his third shot, and so on. In general, since the probability that both men will miss in a given round is 2/3 × 1/3 = 2/9, the probability that Mr. White wins in the first round is 1/3, the probability that he wins in the second round is (2/9) × 1/3, the probability that he wins in the third round is (2/9)2 × 1/3, and so on.

In general, we find that the probability Mr. White wins when facing Mr. Gray is 1/3 × (1 + 2/9 + (2/9)2 + (2/9)3 + ... ). The value of the geometric series is 9/7, so the probability is just 1/3 × 9/7 = 3/7. That is, when facing off against Mr. Gray directly, Mr. White has a 3/7 chance of winning (assuming Mr. White shoots first).

How are these calculations relevant to the matter at hand? Well, we can analyze the outcome of the truel depending on Mr. White's initial action by using some tree diagrams. Let's first see what happens in the simplest case when Mr. White intentionally misses. In this case, Mr. Gray will shoot, and either he will hit Mr. Black or he will miss:

Here, GHB and GMB stand for "Gray hits Black" and "Gray Misses Black," respectively.

Here, GHB and GMB stand for "Gray hits Black" and "Gray Misses Black," respectively.

We know that if Gray hits Black, we will now be in a face-off between Gray and White. Similarly, if Gray misses Black, Black will in turn kill Gray, putting us in a face-off between Black and White. Since we calculated the probability of White winning in either one of these face-offs, and since Gray has a 2/3 chance of hitting Black, this diagram shows that the probability White will win must be 2/3 × 3/7 + 1/3 × 1/3 = 25/63, which is roughly 39.7%.

What if White shoots at Gray instead of shooting at Black? In that case, the picture gets a bit more complicated:

In this case, if White hits Gray the truel will end, since Black will hit White with certainty. Therefore, the only way White can win is if White misses Gray - but in this case, the situation is just as it was before, when white shot to miss. Since White has a 2/3 chance of missing, and from above we know that White has a 25/63 chance of winning if he misses, this shows that the probability of white winning is 2/3 × 25/63 = 50/189 in this case, or roughly 26.5%.

Finally, if White shoots at Black, we get an even more complicated tree diagram:

Notice that the probabilities in the bottom half of this diagram are the same as in the earlier diagram, and therefore it suffices to consider what happens in the top half. Here we see that White can only win if he hits Black, if Gray misses White, and then White wins the face-off against Gray. Following the probabilities on the tree, we see that the odds of this happening are 1/3 × 1/3 × 3/7 = 1/21. Therefore the total probability that White will win if he shoots at black is 50/189 + 1/21 = 59/189, which is roughly 31.2%.

From this analysis, we see that White's odds are significantly increased by shooting to miss: 39.7%, versus 31.2% if White shoots at Black and a paltry 26.5% if White shoots at Gray.

Another interesting feature of this problem is that by shooting to miss, not only does White maximize his chances of winning, but he also becomes the most likely person to win. Using similar arguments, one can show when White shoots to miss in the first round, the probability that Gray will win drops to 38.1%, and the probability that Black will win goes down to just 22.2%. In other words, using this strategy not only makes White the most likely to win, it makes Black the least likely to win, even though Black is the strongest marksman!

As discussed in the Wikipedia entry on truels, there are other variants one can consider as well. One could change the order of the shooters, for example, or toy with the probabilities involved. One could also consider more realistic situations in which the players have only a finite number of bullets, or think about what happens if the players fire simultaneously rather than sequentially. These variants will lead to generalizations of the phenomena observed here.

As with much of mathematics, this recreational problem shows that once you start digging, there's practically no limit to the questions you can ask and answer with a bit of mathematics. Here's to Martin Gardner, for providing us with such a delicious taste of the bounty mathematics has to offer.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus