A Variant of the Traditional Football Pool

Update: Part two of this three-part series on football betting pools can be found here. Part three is here.

During this month's Super Bowl, like many of my fellow Americans, I participated in the great tradition of the football pool. This method of betting on a football game is quite simple. For those of you who have never partaken in this activity, here's how it works:

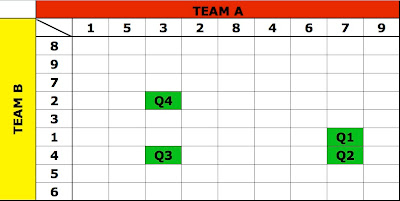

- You begin with a 10 x 10 grid of empty squares, which you auction off at a certain price ($1 per square, say). When someone buys a square, they put their initials in that square.

- Once all the squares have been purchased, each row and each column in the grid is randomly assigned a digit from 0 through 9. This means that each box will correspond to a unique pair of digits, from the 0-0 square through the 9-9 square. Since the assignment is random, there is no way of knowing which digits will correspond to your square when you purchase it.

- At the end of each quarter of the football game, the last digit of each team's score is used to determine the "winning" square for that quarter. For example, if the score after the first, second, third, and fourth quarters are 7-10, 7-13, 21-13, 21-20, then the winning squares would be the ones corresponding to 7-0, 7-3, 1-3, and 1-0, respectively.

- The person with the winning square then wins a certain amount from the pot. It's common to weight the payouts so that the winning square for the final score gets more money than for earlier quarters, but this is not necessary. For example, you could say that the winning squares for the first three quarters each win 20% of the pot, with the winning score for the last quarter winning the remaining 60%, or you could say that each winning square wins an even 25% of the pot - these percentages can vary from pool to pool, but they are made clear at the outset.

If you have any knowledge of how football games are scored, it may seem to you that certain squares are more desirable than others. For example, you may guess that the 7-0 square and the 0-7 square will come up as winners more often than, say, the 2-2 square, since football scores that end in 2 are much less common than football scores that end in 7 or 0.

However, it seems reasonable to assume that this effect will diminish in later quarters, because as the scores increase, the possibility for variation in the second digit also increases. In other words, after the first quarter, the number of possible scores for the game will be fewer than the number of possible scores at the end of the last quarter, because the longer time means that there is more opportunity for scoring, and therefore a larger set of possible scores.

This gives rise to a natural question: on average, are the last digits in a football score distributed evenly between 0 and 9? If not, is there a different way we could conduct the pool that would yield more uniform results?

Of course, there is excitement in the fact that once the numbers have been revealed, some squares will be more popular than others. If you have the 0-7 square or the 7-0 square, suddenly your odds of winning will have jumped up, whereas if you're stuck with the 2-2 square, your chances are practically nil. (In fact, Doug Drinen crunched some numbers back in 2005 by looking at the scores for all football games since 1994, and found that the chance of winning the fourth quarter with a 7-0/0-7 square was about 3.8%, versus a dismal 0.04% for the 2-2 square.) This disparity between squares, however, means that the unlucky people who get the squares less traveled will have less of a stake in the game, and perhaps enjoy it less because of this.

Here's one simple alternative to the traditional pool described above: instead of looking at the last digit of the score when determining the winning square, what happens if you look at the sum of the digits? With this system, a score of 14 would have the sum of its digits equal to 1 + 4 = 5. So, for example, if the final score was 14-21, this would correspond to the box at 5-3, rather than the box at 4-1.

What about a score like 39? If we add the digits here, we get 3 + 9 = 12. In a case like this, simply add the digits again: 1 + 2 = 3, so 39 would correspond to the digit 3. You'll never need to add the digits more than twice, and after this process you'll end up with a digit from 0-9, so the same grid will work. If you want to sound impressive, you can refer to this process as calculating the digital root, and since I want to sound impressive, I will use this terminology throughout. So, for example, the digital root of 39 is 3, the digital root of 68 is 5, the digital root of 17 is 8, and so on.

There is one slight hiccup when using the digital root: namely, the digital root of a number is 0 if and only if that number is itself 0. This means that any box associated to a 0 on the row or column will only be a potential winning candidate if one team remains scoreless.

One way to overcome this slight complication is to simply ignore the digit 0, and make a 9 x 9 grid with digits from 1 to 9. Most of the time, this will be fine, especially later in the game when it is unlikely a team will have no points. In the event that you do encounter a 0, I'll explain two possible solutions below.

Why might we expect the digital root to give us a more uniform distribution of values than simply looking at the last digit of the score? Well, think about the way football is scored. In the game, a touchdown and a field goal will (usually) result in a 10-point increase to the score. So, for example, if the score is 10-7, and the winning team scores a touchdown and a field goal, the score will likely be 20-7 - this is nice for the winning team, but not so interesting for those in the pool, since this has no effect on which square is winning (in either case, the winner is 0-7).

On the other hand, using the digital root, the winning square corresponding to a score of 10-7 would be 1-7, while the winning square for 20-7 is 2-7.

This is but one example, but it is useful in guiding our intuition. Is this indicative of a larger trend? This may suggest that using the digital root gives a more uniform distribution among digits, but is this really the case?

To answer these questions, we can turn to our trusty friend, mathematics. The Football Database provided me with the final scores for every football game during the 2008 season (including preseason), and this is the data I have used as the basis for the following results. Note that because I only used scores from the end of the game, everything here applies only to the final winning square. Also, there's no doubt that I could get more accurate data by compiling data over many seasons, but I don't really have time for that, and one season gives enough data to paint an interesting, if not entirely complete, picture.

Here are the questions the data addresses:

- Does the traditional football pool lead to tallies which are evenly distributed at the end of the game (i.e. is it just as likely to have a team's final score end in a 2 as it is a 7)?

- Does the football pool that uses the digital root lead to tallies which are evenly distributed?

- If both 1 and 2 are "no," which method gives something closer to an even distribution?

The data gives fairly definitive answers to all of these questions. In the 2008 season, there were 332 games played (including pre- and post-season), yielding a total of 664 final scores. Of those final scores, 120 ended in 0, 63 ended in 1, and so on. Similarly, 9 of those final scores had a digital root of 0 (i.e. 9 games had one team go scoreless), 85 final scores had a digital root of 1, and so on. The results are summarized in the following table:

| Digit | Traditional Pool | Ditial Root Pool |

| 0 | 120 | 9 |

| 1 | 63 | 85 |

| 2 | 21 | 71 |

| 3 | 92 | 76 |

| 4 | 113 | 75 |

| 5 | 27 | 80 |

| 6 | 69 | 85 |

| 7 | 114 | 84 |

| 8 | 42 | 81 |

| 9 | 48 | 63 |

What can we learn from this table? Well, it's clear from the second column that the last digit of football scores certainly don't seem to be evenly distributed. Some digits, such as 7 and 4, have much larger counts than numbers like 2 or 5.

What about for the digital root? In this case, the numbers appear to be much more evenly distributed, with the exception of 0, but this is to be expected. Aside from 0, the digit which appears to deviate the most is 9, with only 63 final scores having this digit as their digital root.

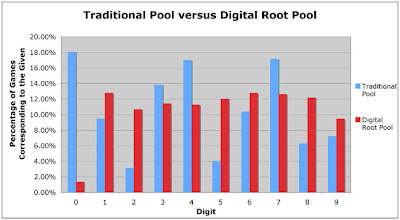

If you're one for pictures instead of words, this graph can help to visualize the discrepancy between these two methods. Here I've divided the counts above by 664 to yield percentages in the graph:

The blue bars, showing the percentage of scores that ended in a particular digit, are visibly less evenly distributed than the red bars, which show the percentages of scores that correspond to a particular digit using the digital root.

This is all well and good, but what if 2008 was just a strange year for football scores? To eliminate all doubt, I tested the probabilities for the traditional pool against the null hypothesis that all the probabilities should be equal (i.e. the probability that a score should end in a certain digit is 10%, regardless of the digit). The result? The odds of getting such uneven percentages if the last digits of the scores truly are evenly distributed is essentially 0%1. From this, we can safely reject the null hypothesis and conclude that looking at the last digits of football scores will not give you numbers that are evenly distributed among the digits from 0 through 9.

How about with the digital root method? To answer this question, we need to know how to deal with that pesky 0 digit, which clearly skews the data. Here were the results under two different sets of rules governing what to do with 0.

In the first case, I simply ignored the scores that were 0. This amounted to only 9 scores, so I was still left with a sample of 655 scores. To these scores I conducted the same analysis as I did with the traditional pool, but in this case the null hypothesis increases each digit's probability from 10% to 11.1%, since there are only 9 digits to consider rather than 10. Here, the odds of getting the percentages above if the digital root of the end game football scores are evenly distributed are about 34%2. In other words, we can't reject the null hypothesis in this case - it may be that the digital roots lead to an even distribution between the digits from 1-9.

In the second case, I combined the nine zeros into the count of scores with digital root 9, since of the digits from 1-9, 9 occurred with the lowest frequency. With this method, the odds of getting the percentages above if the digital root of the end game football scores are evenly distributed jumps to 63%3. In either case, we can't reject the null hypothesis that the digital roots don't become evenly distributed.

Alternatively, you could simply distribute the zeros randomly between the remaining digits - but this should give a probability that is roughly the same as in the first case.

In summary, using the traditional football pool, the second digits of the scores most certainly do not become evenly distributed between 0 and 9. However, it's quite possible that the digital roots do become evenly distributed between 1 and 9, regardless of the choice we make in how to deal with the zero scores.

Does this make the digital root method "better" than the traditional method? Well, it depends on what you're looking for in the football pool. Certainly the data suggests that on average, the digital root method will hit the squares that are rarely hit by the tradition pool with more frequency. However, this is a result that holds true on average, so this analysis can't say whether or not the digital root method will make individual games more exciting. It does, however, seem to make the less popular squares slightly more popular, and the more popular squares slightly less popular. With the traditional pool, if you get stuck with the 2-2 square, you can basically kiss your money goodbye. But with the digital root method, there is still a glimmer of hope that you will prevail.

While he may be best known for his football games, who could forget the classic "John Madden Math '92,"

While he may be best known for his football games, who could forget the classic "John Madden Math '92,"which became an instant classic for both the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis?

Here are some further questions. I won't address them here, but may tackle them later.

- On average, is one team's score in a football game independent of the opposing team's score? Knowing this question would help in calculating probabilities for these pools. For example, if you really want to estimate the probability that a 7-1 square will win, you must take a sample of games, count the number where the 7-1 square wins, and divide by the total number of games. However, if the scores are independent, the probability that 7-1 wins would simply be the probability that one team's score corresponds to 7, times the probability that the other team's score corresponds to 1. This would make for less counting overall, since once you knew the frequency of all the digits, you could calculate the probabilities for all the boxes, rather than counting up the frequency of wins for each individual box.

- What can we say about the difference between these two methods of making a football pool for an individual game? One could easily argue that if the digital root method leads to more different squares being hit during a game than the traditional pool method, it would be preferable, since hitting more squares during the course of the game would mean that a larger number of people had a stake in the score at some point during the course of the game. So, can we compare the expected number of boxes that will get hit with the digital root method vs. the traditional pool method? Note that to do this would require more information than was used here - specifically, we'd need data for every time the score changed, rather than just the final scores. This info is readily available online, but I don't yet have the urge to sift through it all.

- How are the numbers distributed in earlier quarters? Based on the data, it's quite possible that the digital root method yields percentages that become evenly distributed, but this is only after the fourth quarter. Might the scores become evenly distributed earlier?

I can't say yet whether I prefer the digital root method to the traditional pool, but it certainly seems to offer a compelling alternative. In conclusion, here is a video of the 49ers from the 1980s rapping about how awesome they are. If only the 49ers of the 21st century could flow as well as these dudes, maybe they would have a shot at returning to glory.

Big ups to Jon over at Food Junta for alerting me to this inspiring piece of NFL history.

1. Using a simple Pearson's χ2 test, one obtains here that χ2 is approximately 188.7. We have 9 degrees of freedom, so this gives the result (probabilities can be calculated in many places online, e.g. here).

2. In this case, we get χ2 is approximately 9.05. Since we ignore zero, this reduced our degrees of freedom to 8.

3. In this case, we get χ2 is approximately 6.15, again with 8 degrees of freedom.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus